I had a shockingly disturbing chat with my dad earlier tonight. I won’t go into detail. Least said, soonest mended, eh!? Anyway, I suppose some aspects of what that was about will be clear from the themes in this post.

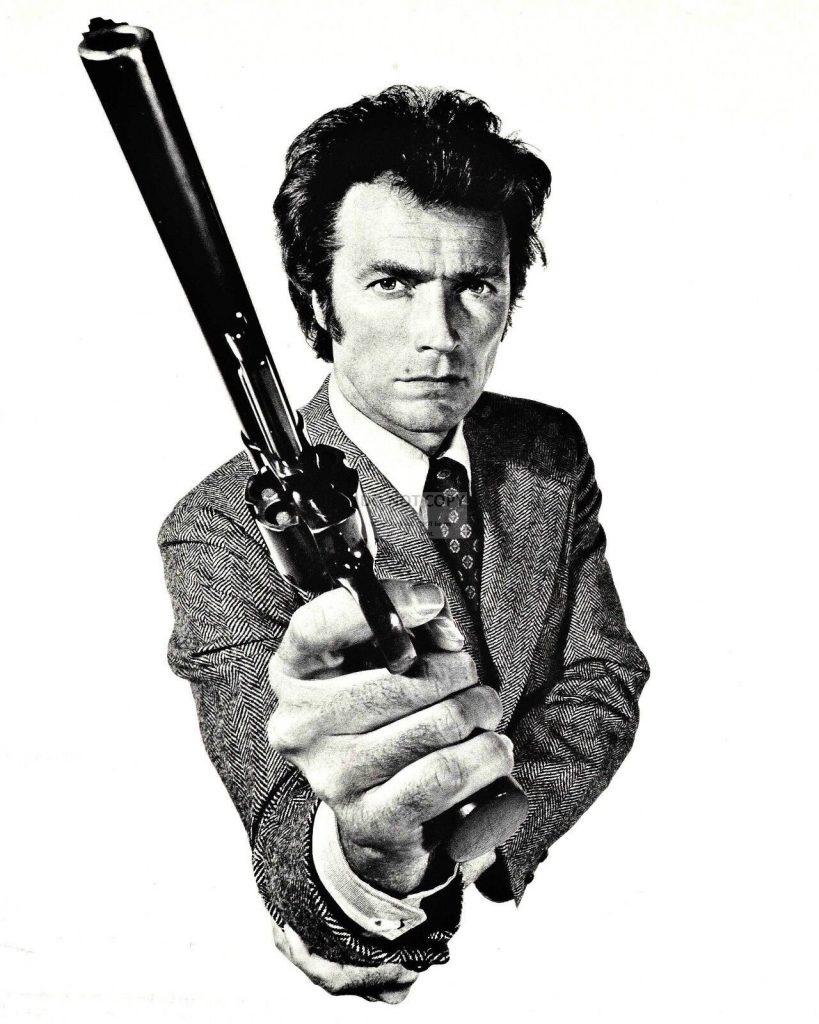

I start with an image that sums up a form of modern hyper-masculinity that would no doubt be described by some nowadays as ‘toxic’. And yet it remains a fantasy that is both persistent and ubiquitous. The lone ‘maverick’ male, short on words, long of gun-barrel. He’ll make a shitty world conform to his will!

And, as silly as they might seem in popular entertainment form – think of Al Pacino at the end of Scarface – the real world is very much affected by such ideas. Boris Johnson thinking he’s Churchill. Churchill thinking he’s St George. St George butchering some rare and endangered winged lizard… and so the cycles of violence roll ever on.

Anyway, I’m going to try and collate some stuff, here on my blog, around the issue of socio-political change, and the role of violence within that.

I don’t think it can be denied that violence has long been a key ingredient (as, on the other hand, is co-operation) in leading to our species ‘enjoying’ the unique niche it has on Planet Earth.

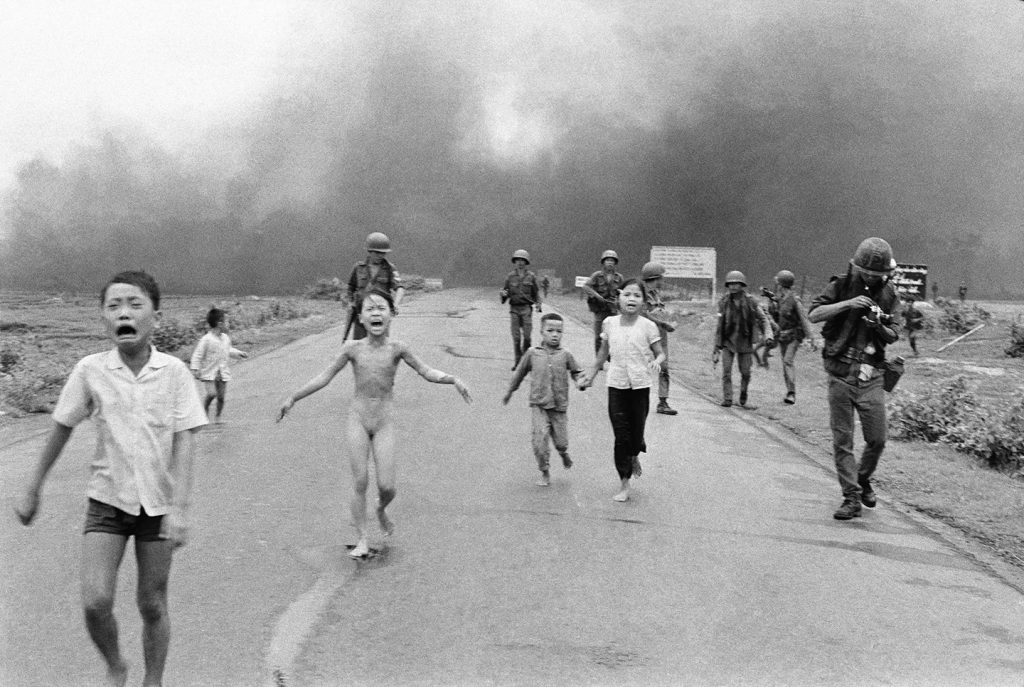

Generalised conflict or all out war have been more or less constant features of our history: whether against our environment, or against each other. Driving change and innovation – from the stirrup to computers – it could be argued that violence has been hugely beneficial to humanity overall, if not admittedly for those unlucky ones who’ve suffered by it.

Ok, it’s stating the bleeding obvious, but violence is, unsurprisingly, pretty much always beneficial to the victor, and pretty much always correspondingly awful for the vanquished.

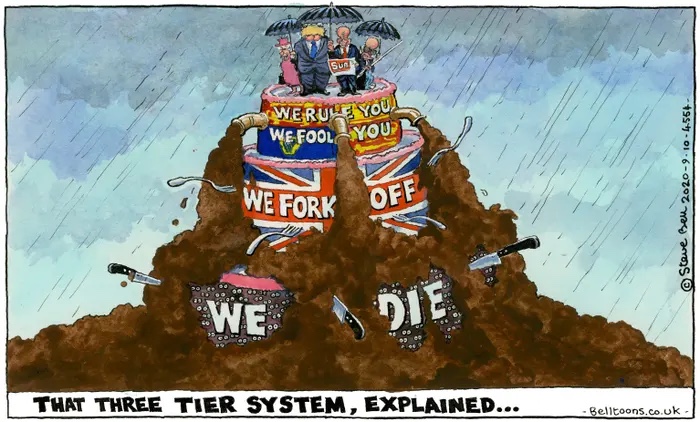

Once again, it’s pretty clear for all to see that violence builds power structures, and very often helps maintain them. But once those structures have been around long enough, does violence, rather like religion, eventually become counter-productive?

I suppose there can be no blanket coverall answers. But I’d like to try and engage my mind (and body) with such issues. It feels like the UK is drifting towards a form of Capitalo-Fascism similar to that which is very alive and (un)well ‘across’ the pond’.

And America as she is today, powerhouse of Capitalo-Fascism, is very much a product of violence. Many of the Europeans that colonised the Americas were fleeing religious persecution in their homelands.

And then a virtual genocide was perpetrated by those European escapees, on the hapless indigenous peoples of that huge landmass, ultimately turning it into the nation it is now.

This Colonial bastard child then had to free itself by war and Revolution from its oppressive unloving ‘fatherland’. And all of that’s before they got to the point of Civil War, whether you believe that was fought over States’ rights to self-determination, or the issue of slavery.

America is a nation – just like all nations are, in truth – born and bathed in blood. It’s the human condition.

Or is it? Many contemporary thinkers believe (or is it just hope?) that there comes a time when violence is, or rather should, no longer be the go to prime mover for human destiny. Such a view is put forward here.

One of the biggest issues in current societies, and again we see it particularly strongly in that fairly young nation, the US, is all about who has the right to ‘own’ violence. America is, to a very great degree, founded on both the idea and the brute reality of an armed self-determining populace.

And yet, when some of the ‘folk’ who feel themselves heirs to such gun-toting ‘founding fathers’ recently stormed The Capitol, it looked very much like a pretty appalling red-neck revolution.

I have to confess I’ve found myself thinking that those who govern us – or oppress and exploit us – may not understand any language other than violence. And those in power have long been thinking similarly. The future enemy may not be other States or Nations (although they remain a useful threat), but ‘the enemy within’.

If ruling elites are too distanced from the suffering they inflict, or allow to happen, they may well wind up in cloud-cuckoo land; blissfully unaware of the appalling realities that they perpetuate, and whose conditions might even be essential to maintaining their own privileged positions.

That’s taking a very generous view. Probably beyond the point of naivety. Another harsher and perhaps more realistic viewpoint would be that the oppressors know all too well what they are up to.

I suppose it is possible that whilst aware, cognitive dissonances can be overcome through the ‘magical’ effects of religious style thinking. Steven Trivers makes a powerful case for fooling ourselves being far more prevalent than we might want to think, in his excellent book, Deceit.

Humans have an appallingly strong tendency to believe in their own own infallible righteousness (even whilst being equally riddled with self-doubt and self-loathing!). Up to a point it’s an essential strength, as it allows us to function more readily, by oversimplifying what might otherwise prove to be insoluble riddles.

The downside is it leads to belligerently partisan tendencies, with all the differing factions believing their particular take on things must be right. This is one of the many reasons I’ve always disliked certainty in people. It just seems too glib. And it’s the first step in dominating others: my truth is so obviously the only truth, how dare you disagree!

And if you’re cowed by this, your adversary or oppressor has won a battle without even having to fight.

I guess right there is where it becomes very interesting. If you’re the oppressed party, you’re immediately cast in a bad and troublesome light, because in order to carve out your own space, you will have to challenge the assumptions (and the consequences that flow from those assumptions) that are being presented to you as ‘just so’.

And of course, returning to a theme alluded to above, but not explored here, it all depends on who perpetrates the violence – state vs individual, left or right wing leanings, racially or religiously motivated, etc. – and what their goals are.

State sanctioned violence to defeat Hitler might conceivably be somewhat different – it’s certainly generally held to be (but is it really?) – from Timothy McVeigh or Ted Kaczynski waging war on a modern society they didn’t like. It’s stuff like this I want to explore in this and other posts here, over time.

But to end on a less gloomily sanguine note, here’s a link to the AEI’s * ‘Liberation Toolkit’. I’ve not read it yet. It might be shite! But I thought it might make a nice counterweight to the foregoing cogitations on violence.

[* AEI – Albert Einstein Institute.]