Wow! What an amazing film. It really is epic. And, rather amazingly, I don’t think I’ve ever seen the entire film before. Sure, I’ve seen parts. It’d be difficult not to have been exposed to at least some snippets of a film that’s so legendary and celebrated.

When you include the musical segments – overture, interlude, etc. – The whole thing is the best part of four hours long. Personally I think that’s part of what makes it a great film. Perhaps like an American celluloid version of Tolstoy’s War And Peace, it takes the time it requires, not to mention the space and the scale, to tell a big story in a big way.

There is a kind of deep irony embedded in the heart of the film. At least as far as I’m concerned. And that’s to do with the juxtaposition of the truly huge stories, to do with the slave-dependant way of life that has ‘gone with the wind’, and the romance. Both are universally interesting aspects of the human story, and both are about social conventions and power structures. Consequently both have a nigh on universal appeal to the viewer.

But the romantic aspect is the more easy to sugar-coat and sell, whilst the slavery/racism side is harder to digest. And the irony I mentioned can be highlighted by the fact that Hattie McDaniel was the first Afro-American actor to receive an Oscar, for her role as Mammy, but she couldn’t attend the première of the film, because … it was held in a segregated cinema. Unbelievable!!

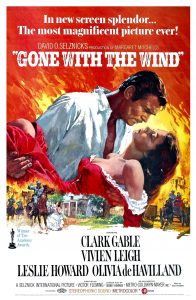

Leaving this shocking aspect of the films history for now, and turning to its aesthetic appeal, the mixture of romance, grandeur, and lush technicolor, make for a winning combo. It’s clear that no expense was spared. There are numerous scenes that really are breathtaking. From the beautiful, such as the views of Tara at sunset, to the awful, like the Confederate open-air hospital, shown below.

Viewed from our contemporary position, some of this remains very effective, whilst other moments are clearly staged. There are numerous scenes in which action occurs against or in what is quite obviously a painted backdrop. The feats of this pre-CGI production remain, however – even in those obviously stagey/fake moments – extremely impressive.

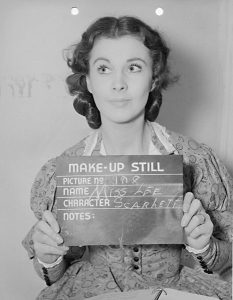

Apparently the film was delayed for numerous reasons, including Selznick’s obsessive desire to get the right people in certain key roles. Vivian Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara and Clark Gable as Rhett Butler are the two key players, of course, and Selznick certainly struck gold with them. They both look the part, and they both play their roles with complete conviction.

Indeed, in this make-up test production photo, Leigh even looks like a convict.

But many of the supporting roles are played with just as much verve, such as Olivia De Haviland as Melanie Hamilton, and Leslie Howard as Ashley Wilkes. Melanie and Ashley are the yin to Scarlett and Rhett’s yang, and in this respect the film is almost operatic in style. Perhaps another reason for the films great success is that it’s almost fairy-tale like in its reliance on archetypes?

Several of the key events of the second half loom with the predictability of classic tragedy: they are seemingly inevitable, and yet lose none of their dramatic or emotional impact. This was the period known to the South as Reconstruction. Although that hardly seems appropriate to the relationship of the two key players here!

I found the film very involving and very moving.

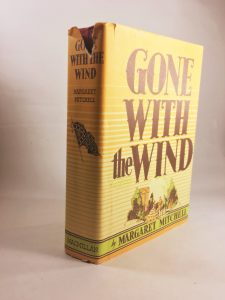

Based on a Margaret Mitchell novel I’ve never read, some of the ideas at the core of the film, and presumably the book as well, are a bit hokey to say the least. Or, worse yet, sentimental and hypocritical, with the Old South portrayed as a land of genteel manners and friendly relations with the slaves. But despite these moral and cultural caveats, Gone With The Wind remains, essentially, a very humane story

It could be deemed trivial or banal, in that it places the romantic misadventures of a vain coquettish Southern Belle over and above the much tougher subject of slavery/emancipation, etc. But just as human power relations between the ‘races’ [2] are an evergreen subject of interest, so to are male female relations. And this no doubt, alongside the lavish production, helps explain the films enduring appeal.

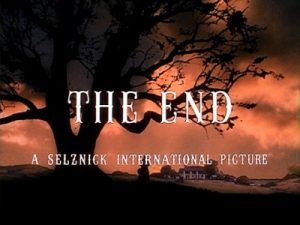

We spread our viewing out over two evenings, our intermission being more or less 24 hours. When the end finally came, it really had been an awesome rollercoaster of a ride. And it didn’t feel too long at all. Indeed, in some ways the ending cries out for more.

NOTES:

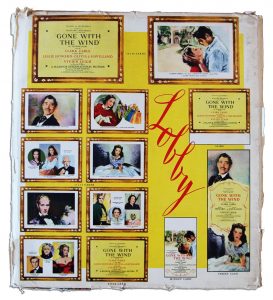

[1] This photo is terrific in that it captures, solely in facial expressions, the open candid innocence, or the what you see is what you get nature of Melanie, and juxtaposes it with skittishly moody and ever changing mirage of Scarlett’s countenance.

[2] Some current science writers argue that race, as commonly understand in human terms, is a false category, and therefore – ironically (and logically paradoxically) – inherently racist.