NB: This is another archival post, albeit slightly modified for inclusion here. I’m an Amazon Vine reviewer, and was sent this book several years ago. I’m winding down one of my other older blogs, and gradually transferring content from there over here.

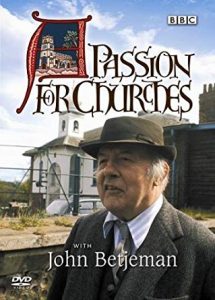

Teresa and I like visiting ye olde churches on our travels. They are usually peaceful places, and sometimes quite beautiful. This is my thoughts on a great guide, written by poet and church-freak John Betjeman, which I was fortunate enough to be given a free/review copy of.

Betjeman’s original book* covered twice as many churches (approximately 5,000). Unlike the first edition, this newer shiny hardback coffee-table version is lavishly illustrated, and as a result cuts the number of churches covered in half, at roughly 2,500… still plenty!

And even if we were to disregard all of this cultural heritage mallarkey, some churches are just very beautiful. Okay, maybe not the one pictured above! More on that in the accompanying footnote, below. Certainly I’ve often enjoyed stopping at a random church and wondering around inside, connecting in my own quiet, personal and meditative way, with all that life and history. So, when offered this on Vine, it was a must have.

I confess I know precious little about Betjeman outside this book, except that he was a poet – indeed Poet Laureate for a while – appeared on the BBC a lot years ago, and is known for rhapsodising about trains. When reading his introductory essay I was struck by how he chooses to spell the word ‘show’ using the rather archaic British variant ‘shew’. Fittingly eccentric and antiquarian, but perhaps also mildly irritating. Why? Well, I feel, and indeed my brain is wired, through learning commonplace English, to think that it should be pronounced to rhyme with shrew, stew, brew, or even, for that matter pew.

In light of this I was not initially sure I could go with the TLS quote on the cover, which effusively describes Betjeman’s introductory essay as ‘pure gold’. In fact at first I found it rather crabbily and fustily conservative – rather like some of the church wardens you may bump into when visiting churches using this book – if very erudite and occasionally quite funny, as for example: “If the path leading… wealthy unbelievers … key from there.” (p23) Well, that’s certainly priceless, but not necessarily because it’s ‘pure gold’!

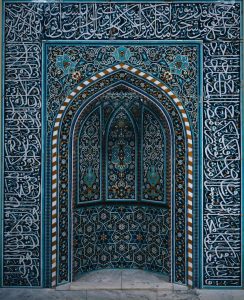

As well as making some very prescient remarks he also says a few things which, to my mind at least, are a little odd, such as “It must be admitted that spirituality and aesthetics rarely go together.” I guess this depends on you how you define spirituality, a nebulous term at the best of times. But many admirers of culture, including eminent scholars of religion, for example Diarmid MCulloch, stress the great contribution religion makes to our aesthetic culture.

Quite apart from our own largely Christian heritage, which has plenty in it that’s clearly paganism absorbed and transformed, one need only think of the incredible non-figurative arts of Islam, the rich iconography of Buddhist mandalas, or the great traditions of religious music, to wonder if perhaps Betjeman has made a mistake with this particular pronouncement.

In the context where he makes this rather bizarre sounding statement, it does actually make sense; lamenting the more recent restorations and additions to a church that are, by and large “practical and unattractive” (ugly modern heating, and P.A. equipment, and the like), he begs that we remember “however much we deplore it … [these ugly things] have been saved up for by some devout and penurious communicant.” Whilst this sonorous phrasing has an appeal, its rendering of the ‘spiritual’ is open to debate. And much of this passage reads like unadulterated Puritanism of a very dull dour sort. Despite England’s break with Rome, I don’t think Christianity, or humanity for that matter, was suddenly and totally bereft of aesthetic awareness. [2]

Indeed, that’s more than half the attraction of this book: these churches are not only frequently very interesting, but also often, in part or in whole, quite beautiful. It is true, there are some horribly oppressive Christian buildings across these islands, and even some of the churches we’ve visited using this book belong in that category, but fortunately they’re in a minority. However, when he follows his line of thought to the conclusion that “Conservatism is innate in ecclesiastical arrangement” I can’t disagree. But perhaps this observation helps define the difference between religion and spirituality?

In addition to a general review, I feel I have to mention at least one church we visited thanks to this book. And there’s really no contest for me as to which that should be. It’s St Wystan’s, Repton, on account of the fantastic subterranean crypt (pictured above).

Returning to the book: “Who has heard a muffled peal and remained unmoved?” Well, ironically part of the appeal of hearing church bells, at least to folk like me, nowadays, is the comparative rarity with which you hear the sound. In the times where I’ve lived close by a regular ringers’ church they have sometimes grown annoying. And what has annoyed me is not that “they are reminders of Eternity”, but that I’m being reminded of a belief which I don’t share, a belief whose omnipresence and omnipotence is, thankfully, receding.

One little technical criticism is that the photos which illustrate points being made in the introductory text give only the village/town name, and then the church name, but not the county. This could very easily been included, and would have been very useful in determining if the church shown is within easy reach. So, for example ‘EAST SHEFFORD: ST THOMAS’, which happens to be on the page I was on when this shortcoming struck me, could so very easily have been ‘EAST SHEFFORD: ST THOMAS (Berkshire)’.

One final note, and an addendum to my original review; Teresa and I moved to the town of March a couple of years back. And St Wendreda’s, March, is one of the churches Betjeman really effuses over, saying it’s worth cycling 50 miles into strong headwinds to visit! I’m not sure I’d go that far. But it does have a pretty splendid roof, with carved wooden angels (see accompanying pics).

A big heavy book, this is more coffee-table campaign planner than handy guide to tote on your travels. Attractive, informative and fascinating, if you find British churches – and it is very much parish churches, Betjeman doesn’t cover cathedrals – interesting or beautiful, or even occasionally both, then this is well worth having.

* Or possibly books? This might in fact be anthologised from a number of church books by Betjeman.

[1] One of several churches we attended during my childhood. Unsurprisingly it’s not mentioned in Betjeman’s book!

[2] This is what Eamon Duffy is alluding to in the title of his book The Stripping Of The Altars. But that’s another whole topic, for exploration some other time and place.