Over Yuletide I watched the Cosgrove Hall animation of The Wind In The Willows. But the version I watched was an augmented and lengthened one, that an enterprising fan had created, splicing in several segments absent from the official release, in order to bring it closer to Grahame’s book, in it’s original unabridged form.

At the time that I’m re-drafting this post (started on my 50th birthday, but totally re-written now, on the 9th), I’m several days into reading this, at an appropriately leisurely pace. And last night, at just gone midnight – a suitably enchanted hour, perhaps? – I read the beautifully titled mid-point chapter, The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn.

The aforementioned ‘extended cut‘ of the Cosgrove Hall production took parts of the TV series they also made, and spliced them into the feature length film that is both a standalone gem, and had also acted as a ‘pilot’, of sorts, to said series. And the insertion of The Piper segment very literally enchanted me.

Some print versions of the book apparently cut this remarkable chapter. Vandalism, I’d say! And I’m not 100% sure, but I think the version I recall from childhood didn’t have that part. As it all felt wonderfully fresh and new to me. Whereas the remainder of the book, by and large, is all very familiar.

As is the way of my adult self, I want to read around the subject a bit. And I’ve discovered that there’s a great deal of tragedy in the real world back story, regarding Kenneth Grahame himself, and most especially as that relates to Alistair ‘Mouse’ Grahame, the author’s son, and only child. It was out of bedtime stories told to the young ‘Mouse’ that WITW grew.

But I’ll save any further thoughts on that and other extra-literary considerations for another time. This post is intended as a very positive celebration of what’s best and most captivating about this classic of so-called children’s literature. I put things that way because it’s my view that the inner child lives ‘eternally’ within us. Or ought to. And by eternally, in this context I simply mean as long as we live, and despite our ageing.

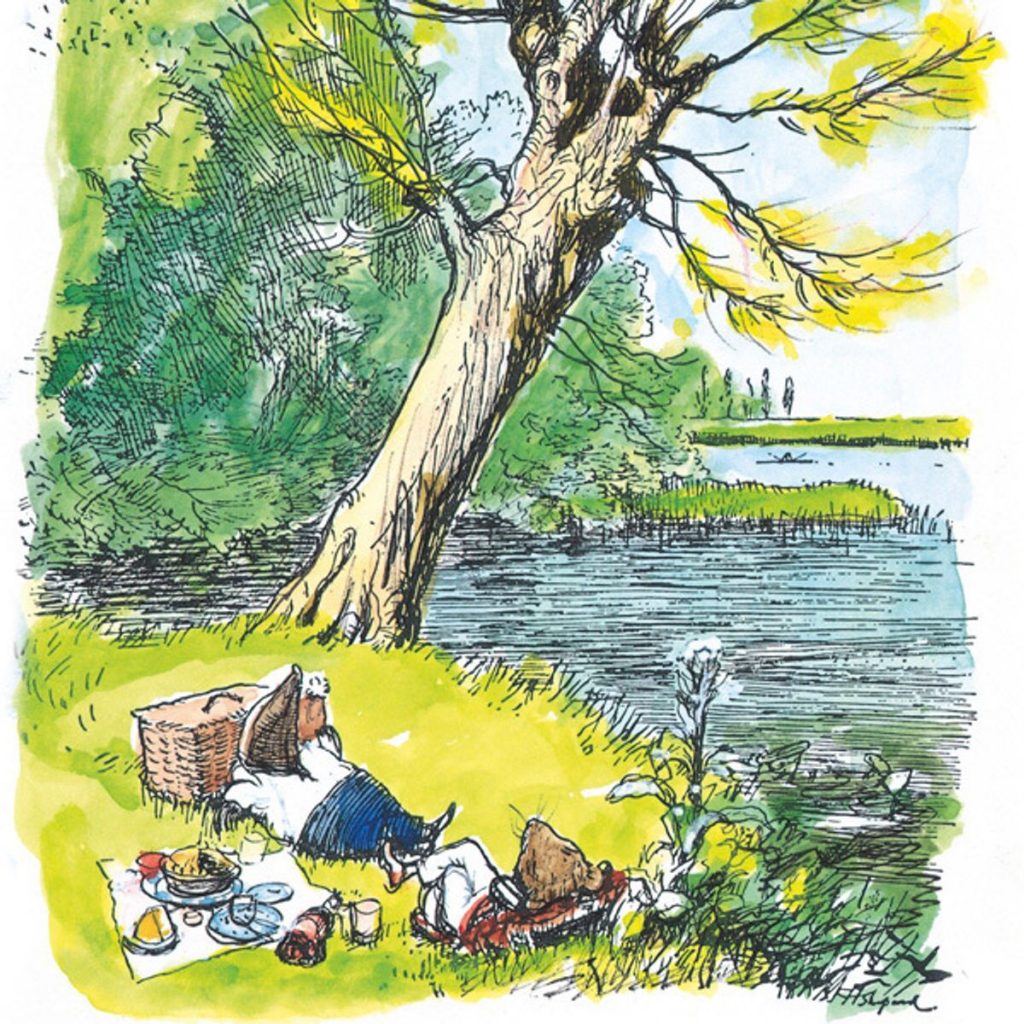

One of the many very attractive things about The Wind In The Willows is it’s strongly pagan affinity for nature. This is something it shares with other writers, such as A. A. Milne – whose stage adaptation of Grahame’s work helped popularise it – and, very notably so, for me at least, J. R. R. Tolkien.

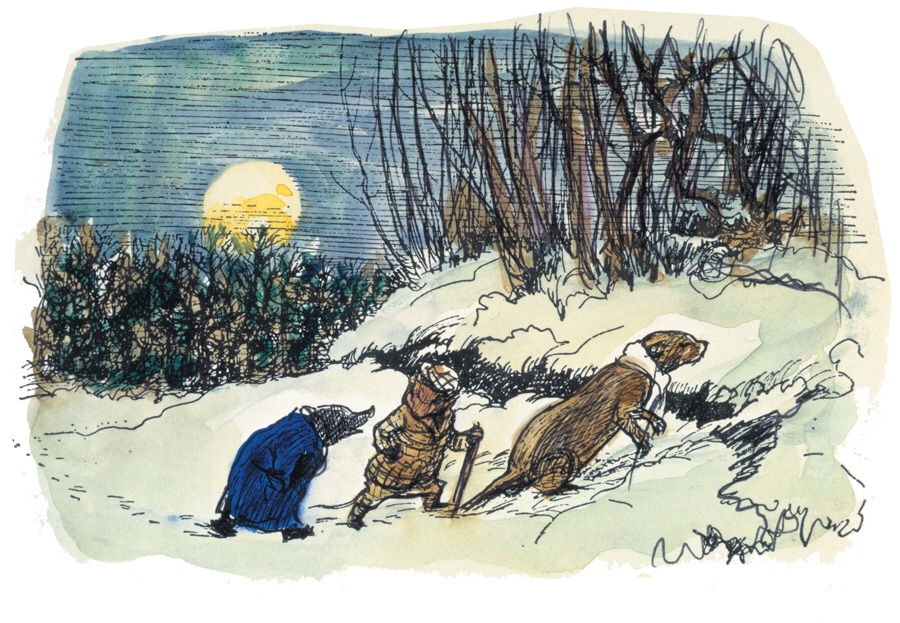

Allusions to Christianity do intrude here, however, and more nakedly so than in Tolkien’s Middle-Earth writings (or the Winnie The Pooh stories, for that matter). But when they do, as for example in the carolling of the field mice at Mole’s door, the frankly comically bizarre parochialism that so frequently attends the conflation of myths, as they travel from place to place and culture to culture, is plain to see, as Joseph and Mary seek shelter in what appears to be some snowy English shire!

Another strand, relating once again to nature and the place of living beings within her, is to do with consciousness. Grahame’s animals, whilst rendered in cutely (or ought that to be acutely?) anthropomorphic forms, retain certain ‘animal qualities’. Or rather what we, or more accurately Grahame, think these might be.

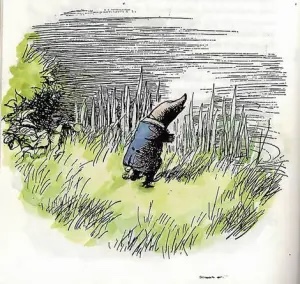

So it is that animals are more firmly located in the present moment. And, correspondingly, perhaps, freed from the burdens of anxiety over past or future, they are more subtly attuned to whole ranges of perception – this is delightfully rendered in the chapter Dulce Domum, in which Mole’s home calls to him on the air, via scent – of which we humans are very crudely and ignorantly unaware.

All of this stuff, from the anthropomorphism to the ideas of animal nature, is freighted with all manner of assumptions. And it’s not set about in a rigorously scientific way. But rather approaches things from a poetic angle. Let’s not forget Grahame also wrote The Reluctant Dragon, about a peaceful dragon who preferred poetry to fighting!*

I absolutely adore The Wind In The Willows. And whilst it may magnify or conceal flaws in the whole romantic view of life/nature, or it’s creator’s own character, or the history of his times, it remains a potently charming work of poetic storytelling art. And, for me at least, it’s manifold attractions far outweigh any nitpicking analyses, past, present or future.

It’s interesting that Grahame, like Tolkien, found finding a publisher difficult. And it’s worth noting that TWITW was no overnight success. Indeed, at the time of first publication it received poor to indifferent notices!

Anyway, this post is intended to capture the flashes of enchantment that this terrific little gem of book lit up for me. I’ll leave it there for now, as I still have just under half the book left to read.

* Also brought to our TV screens, and delightfully so, by Cosgrove Hall!

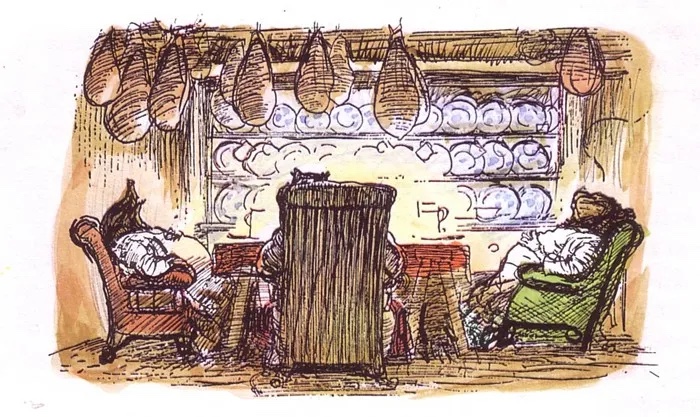

I ought also to mention the absolutely wonderful illustrations, by E. H. Shepherd, with which I’ve enriched this post. They are pitch perfect.