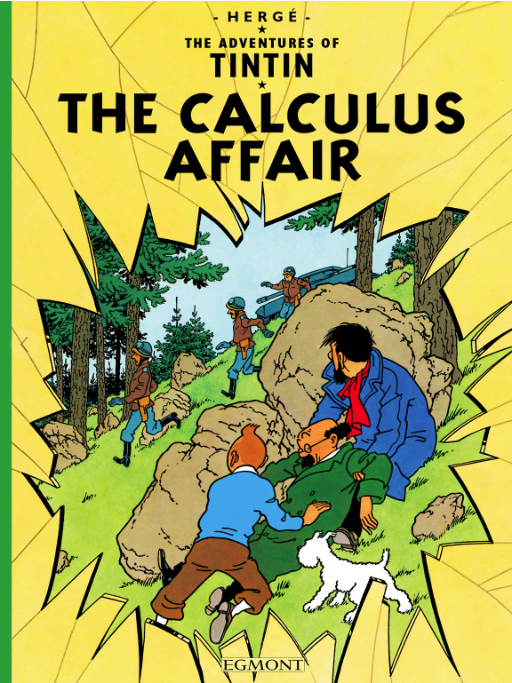

From the peak period of Hergé’s latter career, The Calculus Affair is definitely amongst my personal favourites.

Ever since he first appeared on page five of Red Rackham’s Treasure, professor Cuthbert Calculus bumbled right into this Tintin reader’s heart. Unlike some Tintin characters (Haddock being a notable example) who take a tale or two to ‘settle in’, Cuthbert arrives fully formed, combining elements Hergé had previously dabbled with in other characters, notably the scientists and academics like Professor Alembick in King Ottokar’s Sceptre, or several of the characters in Tintin and the Shooting Star.

Cuthbert’s place in Hergé’s own heart is clearly evidenced by his central roles in all three of his ‘double-bill’ adventures: having introduced him in the sequel to The Secret Of The Unicorn (the aforementioned Red Rackham’s Treasure), he is a key character in both the strangely occult-themed south-American adventures of The Seven Crystal Balls & Prisoners Of The Sun, and the absolutely brilliant and more scientifically-themed Destination Moon & Explorers On The Moon, in which he really comes into his own as a fully-fledged central character.

Having already been abducted once before, in the South American double-bill, Calculus is again ‘disappeared’, in the magnificent Calculus Affair, this time not for ‘meddling’ in the traditions of a primitive superstitious culture through his archaeological and anthropological work, but because he discovers a technology with a military application.

Hergé gets to return his characters to a former theatre of operations, that of King Ottokar’s Sceptre, only this time it’s Borduria instead of Syldavia, and he’s freer, post WWII, to make the ‘Taschist’ regime a blatant critique of dictatorship, combining elements of both left and right-wing forms of absolutism (as exemplified by the Nazi style arm bands worn by ‘Taschists’, and the sinister Eastern block vibes of Col. Sponsz’s secret police, the ZEP, dressed in Green like Soviet troops, whose very name as well behaviour suggests the KGB).

Almost every frame can be admired as a work of great art, making this a sublime visual feast, and the story flows beautifully, disguising well it’s episodic structure. By this stage even the incidental characters are well fleshed out, meaning cameos such as that of Italian motoring-enthusiast Arturo de Milano are thoroughly engaging.

Over the years Hergé experimented with occasional full page artworks or frames, or sometimes, as in this instance, and very successfully, with ‘oversize’ frames. In The Calculus Affair, already one of his best drawn Tintin adventures, there are two such frames, both of which are delightfully detailed, full of wit, character and invention, capable of sustaining long attention and admiration.

Full of incident, action, humour and humanity, this is – for my money – one of the very best of a series which is itself of an unusually high and overall consistent standard.