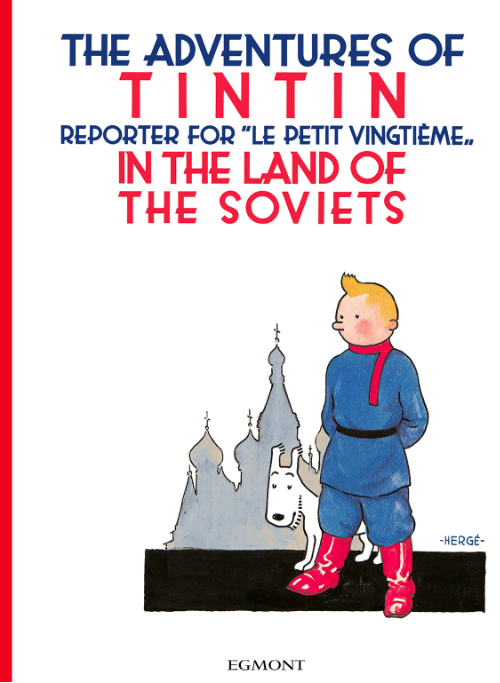

Tintin’s first adventure to be published in a full book form (or rather album, as they were called), In The Land Of The Soviets is even more anomalous than it’s better known somewhat infamous follow-up, In The Congo, for several reasons. First of all it was never deemed worthy of a redraw, which might’ve seen it truncated to the normal length and format all the other Tintin albums share (62 pages), and would also have seen it colourised. So, at 141 pages, and in black and white, it remains an oddity in purely technical terms.

And not only this, but as a story, and as a work of art, it also differs markedly. Rather than hearing Hergé’s own voice, which only really comes through in the gentler humour (in itself mostly rather lame on this occasion, and also often anything but gentle: along with In The Congo, In The Land Of The Soviets finds Tintin at his most brutal), we are served up a very heavy handed dose of anti-Communist propaganda: Hergé is certainly the ‘company man’ at this point, doing the bidding of his Catholic employers. After this story, only his adventure In The Congo makes any explicit reference to the paper – Le Petit Vingtieme – for whom Tintin is allegedly a reporter. In fact In The Land Of The Soviets is also one of the very few Tintin adventures in which we ever see him writing up a report, to send back to the paper.

In addition to all of this, Hergé’s craft is very much in its infancy, which makes In The Land Of The Soviets an interesting rather than particularly satisfying document. The drawing, dialogue, and storytelling are all, by Hergé’s own later standards, really quite poor. In fact one of the most noticeable shifts in the whole catalogue of his Tintin work is the almost quantum leap between this and In The Congo, especially in terms of the artwork, but also in most other respects. Some aspects, such as the smoothing out of the episodic structures that originated with the weekly serial format, would take longer to iron out and improve. But there are precious few hints – some gags that will be recycled later, the odd well composed frame, or series of frames – of what was to come later. On the evidence of this adventure alone one would hardly predict the great lifetime achievement, with Tintin as the primary vehicle, that Hergé actually went on to.

Even more of a one-for-the-fans curio than In The Congo, but perhaps less so than the unfinished Alph Art, this would not be a recommended starting point for those coming fresh to Tintin. Even Tintin’s character differs from what it was to become, with him being less innocent and more thuggish, only Snowy resembling his character as it would remain (more or less) in future. So, although it was, in book form adventures, where the much loved reporter and his dog started out, I wouldn’t recommend any reader started here.

Still, for Tintin nuts like me, and there are clearly a great number of us out there, this is nonetheless essential.