Neither devil nor saviour…

Ok, I haven’t done this for a book before, here on ye blogge. But then I don’t often post book reviews before I finish the book under review, either, like I did with this one. I had to take a breather on 12 Rules, during which time I read a few other books, such as Peter Burke’s excellent Polymath.

I think the stink I kicked up on FB just around the mere idea I might have the temerity or foolhardiness to entertain the foolish charlatan mummery of this evil purveyor of patriarchy and conservatism drained me of energy and enthusiasm. Plus I found that JP’s incessant recourse to Biblical ‘wisdom’ grated.

But, returning, refreshed and invigorated, from said breather, I found I did actually want to finish 12 Rules. So, er… I did.

Interestingly enough, chapter eleven, which was unread at the time of my last (and therefore partial) review, is probably the one that most directly addresses the more contentious areas he covers, the ones that produce allergic reactions in some on the left. Intriguingly, chapter eleven is also the longest single chapter in the book.

The chapter title, ‘Do not bother children when they are skateboarding’, isn’t the clearest of the twelve chapter headings. I initially guessed it might simply mean ‘let the children have their fun’. And it does. But more than just this, it’s also addressing those that seek to circumscribe the fun those children might have: ‘Beneath the production of rules stopping the skateboarders from doing highly skilled, courageous and dangerous things I see the operation of an insidious and profoundly anti-human spirit.’

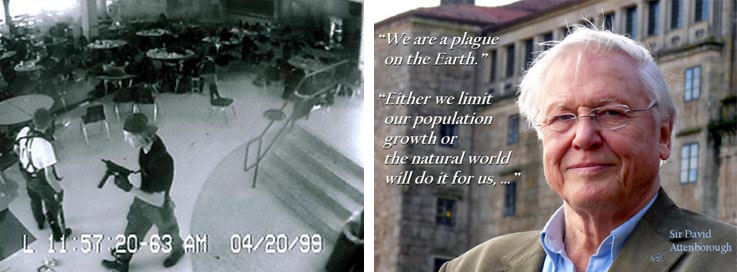

Some of the people Peterson chooses to attack, as exemplars of this anti-human spirit, are not that surprising, such as the Columbine shooters. But others include the much beloved naturalist and TV presenter David Attenborough, and the Club of Rome (a progressive international think tank dedicated to solving global problems). The former for calling humanity a plague the latter for calling humanity a cancer. The nihilism inherent in the actions of the shooters is patently obvious. It’s more shocking to hear Attenborough and a group dedicated to solving the world’s problems described thus, or juxtaposed with ‘postal’ teen murderers.

Clearly at times JP enjoys courting controversy and ‘needling’ his audience. But there is also a very sobering aspect to this. Whilst this is a challenge to those of us who love Attenborough, for all the incredible natural history TV he has given us (and, perhaps even the Club of Rome? Though how many folk even know of them, let alone who they are or what they do?), I think Peterson is on to something, and is essentially correct.

Attenborough and the Club of Rome are, in this instance, perhaps not being precise enough in their speech (and precision in speech is one of JP’s rules). The negativity of their language, designed no doubt (like JP’s juxtaposition of them with serial murderers) for maximum impact/effect, creates a dangerous space.

A dangerous space into which some folk – I was going to say ‘less enlightened folk’; but you can be genius clever and still be wrong – might seek to interpolate their own malevolent answers to the ‘human problem’. Via appalling ‘final solutions’ such as are imagined in say, 12 Monkeys. Casting themselves thereby as heroically ridding earth of the plague or cancer of humanity.

This sort of thinking, taken to it’s most nihilist extremes, was indeed the kind of raison d’etre behind the infamous Ted Kaczynski’s personal war against modern humanity. A very clever chap. Hence the decision not to use the term ‘less enlightened’!

Two other areas where he discusses stuff that seems to trigger hostile reactions from ‘the left’ are around his views on Marxist academia and gender politics/history. He clearly dislikes the whole postmodernist project. And he doesn’t pull his punches, describing it as state-funded extremism whose aim is the destruction of the very same state that supports it.

First off I might ask JP to calm down and substitute ‘transform’ for destroy. Having said that, having been in such an environment myself, studying art and art history at Goldsmiths, where Deleuze, Guattari, Barthes, Horkheimer, etc, were bread and butter, I can see and understand his position. I personally think that much of this stuff is indeed total bullshit, masquerading as intellectualism.

But, and here I may, perhaps, differ from Peterson; whilst they may posture as radicals, I think most academics are innately conservative; they want to stay in their relatively cushy well-paid jobs. The issue is, what does all the relativist, ‘nothing outside the text’ postmodern claptrap become, or facilitate, when it exits the groves of academe, and, like genetically-modified crops, escapes from its own fields, and get out into the ‘real world’?

And here I think Peterson’s fears are better founded. And no, they are not just some paranoid conspiracy theory. Ironically the whole postmodern ‘my truth vs your truth’ relativism actually seems to favour the extreme right – by nature generally more belligerent – at least as much, maybe even more, than the ‘extreme left’.

Another area to address, again coming out of the mammoth eleventh chapter, is gender roles, and our deeper cultural (and social/biological) history.

Some of the very dominant themes being cultivated or promulgated in the kinds of departments in universities that Peterson takes issue with, are ideas such as the whole ‘patriarchy’ narrative, or the popular notion that gender identity and roles are almost entirely culturally constructed.

One of the key themes in the whole ‘Do not bother children when they are skateboarding’, idea is allowing life to continue to have risk and danger within it. And around this idea JP does also address the current trend to constantly run down maleness or masculinity as ‘toxic’, and patriarchally oppressive etc.

I see plenty of evidence of this in daily mainstream social intercourse, say for example on FB, where some women will very openly and regularly complain of the constant oppression they suffer, usually by repeating off the shelf memes on these themes. And an amen chorus of fellow ladies, and a number of men – some will say enlightened, others might say dissembling, or even ‘pussywhipped’, etc. – will provide a hallelujah-chorus. And a frequent contrapuntal theme in such threads will be the mocking of any men who question this narrative, with vigorous suggestions that they are the blind, brutal, entitled oppressors.

I’ve seen Peterson coolly and calmly unpack such ‘arguments’ (in fact they are not usually arguments at all, they are blunt assertions), and dismantle the treasured narrative. And yes, he does the same here in his book, albeit only now and then, and in specific places.

One of his key arguments against the patriarchal oppression model is that what has oppressed women for most of history has not been men, but the natural workings of women’s own bodies. And in more recent times, a number of men have, via their compassion and industry, contributed to the liberation of women from the ‘tyranny’ of their own bodies, via such things as better sanitary products, and the pill. As JP asks, are they part of this all powerful all consuming patriarchal oppression?

Like Peterson, I think a good long look at human history will show that, by and large, ours has actually been a history of cooperation and mutual support between the sexes, in the face of the extreme hardships – and I’m talking now of the more fundamentally physical irrefutably extreme hardships, such as plague, famine, and war, not the more modern ones, which arise once we live longer and are somewhat liberated from the more basic limits on our biological survival.

The division of labour in the human species has rested for vast stretches of time on men doing certain things more, such as hunting and making certain stuff, and women doing other things more, mostly around the domestic sphere of child-rearing and food preparation, etc, albeit with a good deal of overlap, no doubt. I don’t personally ever hear JP saying that because this was true, we must therefore continue exactly that way. Far from it, he says we need to rework what we inherit from the past and continue to adapt to our own peculiar set of circumstances.

Viewing the past as having been predominantly cooperative between the sexes, as opposed to one long unceasing dominance and exploitation of men over women, seems to chime better with the evidence.

This is not to say that in recent history there has been no discrimination and imbalance between the sexes. There is plentiful evidence that there has been. What doesn’t seem right is to counter one form of imbalance with another. There is also a need to learn to be able to recognise things for what they are, not what we wish them to be. And perhaps ideas of totally uncircumscribed ‘freedoms to choose’ are illusory (or even worse, harmful?).

Another problem with the ‘oppressive patriarchy’ model, as I understand JP’s critique of it, is that it can give an appearance of having nothing positive to say about masculinity. And that is inevitably as lopsided and bad a stance as a male-chauvinist position. But, truth be told, much of what I’ve digressed into here really isn’t what this book is about.

Anyway, now that I have finished the book, I don’t find myself convinced that Peterson is a dangerous alt-right idealogue. Far from it. He does have some views that are what some might call ‘innately conservative’, such as that much of what we inherit, to our benefit (as well as detriment), from those who’ve been before us, whether that’s in the form of myths that might contain traditions of wisdom (for JP Christianity is one such), or social institutions, such as marriage, might be better than a complete abandonment of such things, to be replaced by a free for all. I don’t find such observations, especially if couched in the terms of traditions of contemporary science, i.e. supported by evidence, very threatening or troubling.

Unlike JP, I’m not a massive fan of the Christian religious tradition. I suppose aspects of such relationships will often boil down to one’s own personal experiences of these traditions. For me the Christian tradition has for too long been used too oppressively, and been taken or treated too literally. And I also believe that a big problem with the poetry of myth, any myth, is that it’s wide open to almost any interpretations. Many of the ways JP chooses to read Biblical stuff in the context of this book would be, to my mind, amongst the best (and most generous spirited!) of possible readings. But the fact that such a body of traditional tales can also be used to bolster positions I find totally moronic or repellent means I prefer to discard the whole thing, more or less.

I think this is a good book, for the most part. I don’t agree with everything Peterson says. But a lot of it I do. There’s a lot of potentially useful wisdom here, mostly around the perennial themes of taking personal responsibility, and working on self-improvement.

And, as he himself says, not directly so much, but in his use of references to religious traditions (mostly, but not entirely, Christian), and writers like Dostoyesky, and philosophers and psychoanalysts, etc, these are not his own original ideas, but long established ones, ones that are – and need to be – continually re-learnt and re-stated, in our cultural traditions.

I would definitely recommend this book. And perhaps most of all to those who think he’s some kind of alt-right nutjob; instead of bringing your preconceptions, listen to what he’s actually saying, try and understand it, and maybe even, as per rule nine, consider that he (or any interlocutor you may encounter) might know something you don’t.

Or he might even simply be restating something you do already know, but forget to put into practise? Anyway. I think I probably will read his follow up. Whilst 12 Rules isn’t perfect, it hasnt put me off JP either.