More dissection than penetration.

More archival reviews from the vaults. This one from 2014.

I got this book because I’m interested in sex. Who – if they’re being really and truly honest – isn’t? Oh, and art and culture, of course! Having flicked through the pages to have a quick look over the pics, I made ready to, erm, get stuck in, so to speak.

My view was immediately arrested by the bizarre pendant of fig. 1, pictured below: ‘Pet Phallus’, c. 100 BC… length 9.2 cm. Even amongst academics and custodians of culture it appears size matters!

However, any idea that this might be an erotic viewing or reading experience, never mind entertaining (a bit of tongue-in-cheek humour – steady! – might not have gone amiss), rapidly evaporates upon reading the text, which is worthy but, frankly, rather dull.

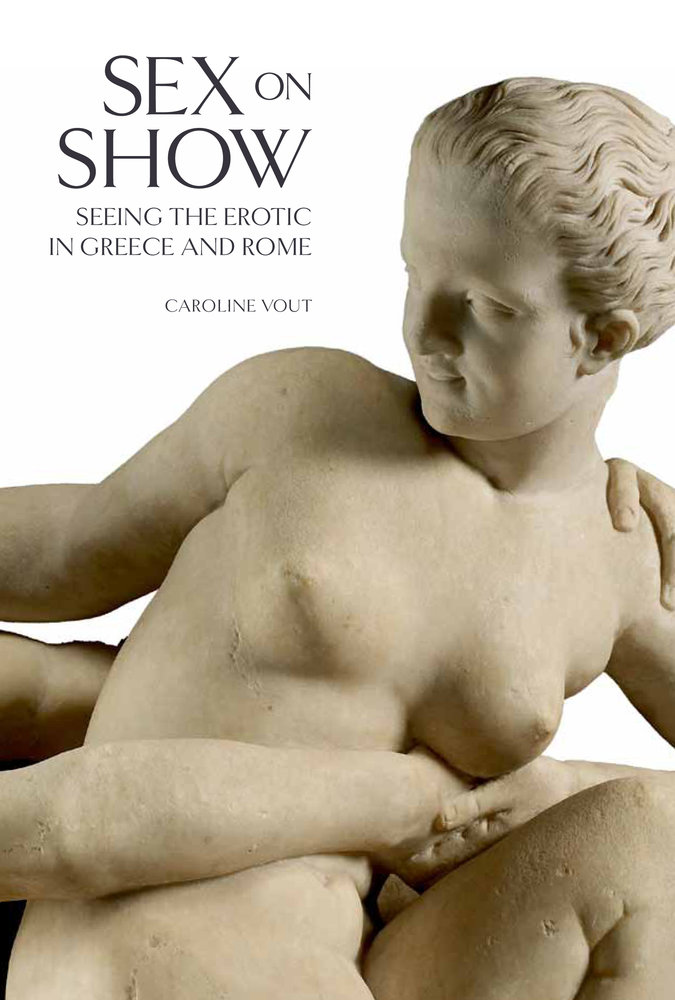

Caroline Vout displays an admirable breadth of erudition, and the text is very clearly and sensibly organised, but it feels a bit flat and lacking in passion. The potential eroticism of the objects and images is rinsed out with academic earnestness; comprehensive and balanced, perhaps, but – for me at least – flaccid.

The book itself, organised into six chapters over approx. 240 pages, and supported by nearly 200 crisp, clear images (as many of these are context-setting as are sexual), is a handsome and well made thing, but I’d say it was beautiful, as opposed to sexy. Some of the images and objects can, as Vout says, still shock and challenge us, despite the pervasive ubiquity of sexual imagery in what some might call our ‘permissive’ culture.

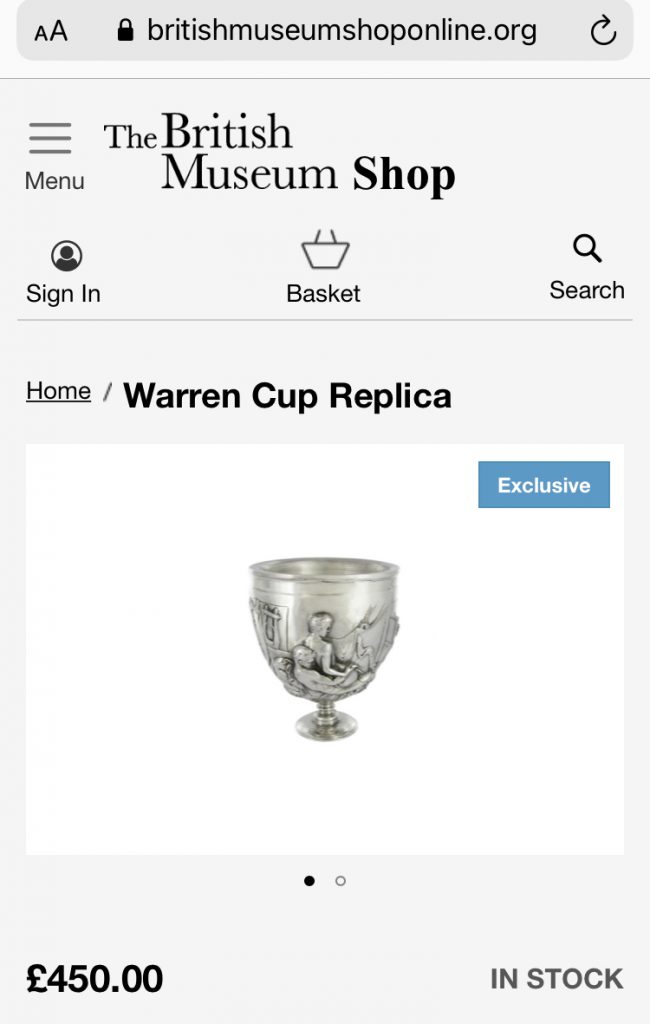

Vout traces the history of these objects, from their contexts and origins, inasmuch as we can determine them, via later fates, including their passage through the collections of private ‘antiquarians’ of the relatively recent past, such as Warren and Townley. It was the collections of such men that stocked the museums they now reside in, the material here being predominantly drawn from the stock of the British Museum, who also published the book.

Having examined how the Greeks and Romans may have related to this material, Vout eventually looks at a range of C18th ideas, from admiration to opprobrium. On the one hand Vout quotes an Enlightenment collector, enthusiast and apologist, who ‘argued passionately for sexual tolerance’, and talks of the ‘noble simplicity of the ancients’, whilst on the other we hear from one of the numerous critics of such collectors, who decries their collections for being filled with ‘generative organs in their most odious and degrading protrusion’!

It’s only very recently that many of these once relatively commonplace objects, and this is particularly true of the more risqué ones included here – which include fairly explicit depictions of bestiality, rape and homosexuality (some taboos evolve, others perhaps don’t) – have begun to emerge from the shadow of our more recent Christian heritage, and find their way into public view, beyond the esoteric confines of the ‘museum secretum’. These changing modes of display reflect evolving values, and the ‘Warren Cup’, for example, has enjoyed an odyssey from ‘controversial’ object of private admiration to British Museum shop souvenir!

For me this book, whilst undoubtedly really quite interesting, and filled with many beautiful objects and images (as well as some strange, some disturbing, and some weird or banal), dissects rather than penetrates its subject, and is, rather bizarrely perhaps, almost sexless.

Towards the end of the book, as she starts to sum up, Vout refers to a Barbican show called Seduced (fairly recent at the time of writing) which she describes as ‘a show which put visual stimulation over and above context’. Vout very avowedly does the precisely the opposite.