Another old review, transferred and updated in minor ways.

As Sam Harris attempts to make clear at the start of his book The End of Faith, what we believe is tremendously important. In Harris’ opening scenario he portrays a religiously motivated suicide bomber. This character feels that by killing a bunch of random strangers, who they – and this is the crucial bit – perceive to be their enemies, they are doing God’s work, and thereby also taking a direct short cut to heaven.

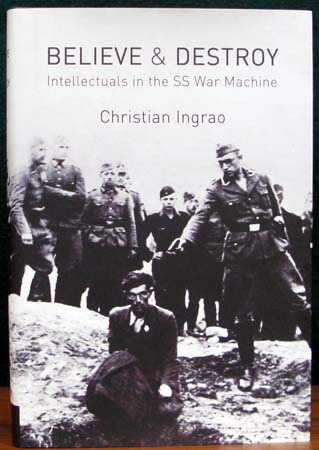

In this book Christian Ingrao is looking at something similar, in relation to what highly educated Nazi intellectuals believed, and how their beliefs became actions: hence his title phrase, believe and destroy. Like the infamous image – known as ‘The Last Jew In Vinnitsa’ – used on the books cover, this is a horrible subject.

But where Harris’ book is an easy read, clearly very much intended for the general reader, Ingrao’s book is based on a thesis written for fellow academics, and consequently is a rather tough slog for the non-specialist. Freighted with specialist jargon and many German terms, and neither written nor translated with ease of readability obviously foregrounded (although some terms are explained in a brief glossary, others in the index, and yet more via translator’s notes, overall the approach is haphazard and hard to follow); it’s interesting and worthy, but often feels like swimming through treacle.

One thread that came through strongly for me, albeit not brought out clearly or specifically by the author, is Nazism’s unholy blend of science and religion: in religious terms, Nazism offered believers faith in ‘the expectation of a racial utopia in which the elect would be made as one.’ This faith aspect was in turn founded on a pseudo-scientific biological racial determinism, in which the continued existence of a superior Nordic/Aryan race is threatened – both directly via conflict, and indirectly via miscegenation – by other races, including Asiatics and Slavs, but particularly the Jews, who are seen as ‘parasitic’.

The supposedly scientific side has several strands, some of these come from the unfortunately named area known popularly as Social Darwinism (unfortunately named because it’s based more on the ideas of Herbert Spencer than those of Darwin), including such ideas as ‘survival of the fittest’ and ‘might is right’.

But Ingrao barely touches upon this side, and deals instead in the scientific side as manifested by academic professionalism, as in data-gathering, compilation, and extrapolation. This aspect sees the SS intellectuals using what might appear to be scientific principles or methods to bolster their own world views.

Actually this is more like ideology skimpily clad in the apparent trappings of science, as the scientific method is (or ought to be) very different: you study the world, and the results tell you what to believe. With these SS intellectuals, you study the world to confirm what you already think. So, effectively what you have in Nazism is the unholy marriage of two of the worst aspects of belief systems: pseudo-science – an ideological natural fallacy – believed in with religious fervour, written in the blood of those perceived to be enemies.

The siege mentality, based on the unfinished business that many Germans felt was the legacy of WWI – and this is a major theme in Ingrao’s book – allowed many German’s to follow the Führer in believing that their active, discriminatory aggression was a defensive act! I would say that this is precisely the kind of mentality shared by Christian crusaders or Muslim jihadists, and more religious and emotional in its basis than rational or scientific, despite the desire within the higher echelons of the SS and the Nazi machine to pass itself off as founded in science. The emotionally driven atavistic völkisch aspects of this toxic creed clearly trump any kind of rationalism.

Unfortunately, the overly florid, windily verbose academic language Ingrao chooses to employ – a typical sentence: ‘They were, in their very subjectivity, an exceptional source for the history of representations’* – clouds what are essentially simple issues, making it all rather tortuously complex. Also, as with Esdaile’s Napoleon’s Wars, or a book I read on Constantine fairly recently, the nature of Ingrao’s choices, in choosing to study the structural and administrative side of the phenomenon under the lense, make for rather dry reading. So, far from being without interest, this is good, solid academic work, but a pleasure to read it ain’t. Put bluntly: worthy but dull.

* This is, in fact, a short and relatively clear/easy example. But it sounds as much (or perhaps more?) like a phrase from a postmodern influenced art theory essay, as it does something that might be said of Nazi ideologues.