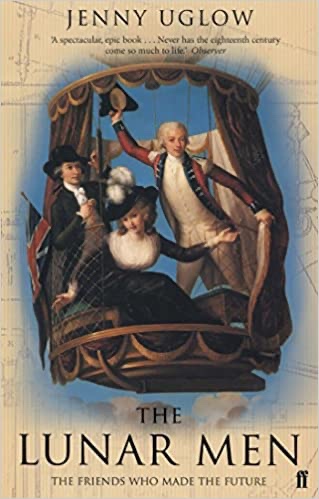

Fascinating book about ‘a constellation of extraordinary individuals’.

Another archival review, from about a decade ago. Again, stimulated to post this now having just read Polymath, by Peter Burke.

The Lunar Men certainly were ‘a constellation of extraordinary individuals’, as Uglow herself concludes in her epilogue to this weighty tome.

It was reading widely about Charles ‘Origin’ Darwin, around the time of his bicentennial (2009), that lead, almost inexorably, to an interest in the Lunar group, with Stott’s book Darwin’s Barnacle sealing the deal, via the chapter on Charles’ grandfather Erasmus. Erasmus figures large in Uglow’s book too – something of a Titan, both literally and figuratively; a man whose interests (and physical girth) seemed to know no bounds! – and learning more about him is fascinating.

But then there are also the many other ‘Lunatics’: Boulton, Wedgewood, Watt, Priestley, Edgeworth, Whitehurst, Keir, Day and several others. Some of these others are very much Lunar Men, whilst others are just passing through their orbit, like American polymath Benjamin Franklin, or Joseph Wright (‘of Derby’) the painter. Whilst not strictly a Lunar Man, as such, Wright, like Franklin, nonetheless figures prominently in the book.

Some of these names will doubtless be familiar to those with a little general knowledge, Wedgewood for his pottery, Watt for his work with steam engines, Priestley for his politics as much his science, and so on. But the lesser known figures are often equally fascinating, from the fussy-in-love Rousseauian romantic and reactionary Day, to the perhaps a little hapless Withering, who gets into a scientific spat with Erasmus Darwin that reminds me a little of that between Dawkins and Gould in our own times.

One of the many fascinating things about the many subjects covered in this book is how they all mesh together at a particular point in time: coming out of Enlightenment thinking, and based (for the most part) far north of London, they represent a growing blurring of old feudal social distinctions and an increased independence (of both mind and pocket), whilst their voracious quest for knowledge connects them to both emerging ideals of political and personal liberty, and the birth of industrialisation and commercialisation, which would simultaneously lift levels of material wealth, and increase ‘alienation’ and the dependence and insecurity of the working population.

Largely pro-liberty, despite the ties of the patronage system many of them cooperated in and profited by, they initially embraced the French Revolution, but as The Enclosures bit deep into the land, and Britain reacted against the threat of revolutionary and then Napoleonic Europe, various aspects of the Lunar Men’s interests fared unevenly: Wedgewood thrived, advancing industry through increased chemical and practical knowledge, and (like Boulton) bringing higher levels of finish to ever wider markets, whilst Boulton and Watt’s steam power quite literally boomed, in every possible respect. And of course Erasmus’ interests in evolution would be picked up and developed by his son, Charles, with epoch-shattering revolutionary effect.

But Day’s reactionary politics and Priestley’s libertarianism (his fate in relation to riots and ‘anti Jacobin’ unrest is rather sad) would both succumb to the strange mix of the pragmatic advances of capitalist industrialism (what Day, along with the likes of William Blake – Uglow uses the lunar theme to connect the Lunar Men’s reaching ‘so eagerly for the moon’ with Blake’s engraving mocking scientific hubris [the famous ‘I want, I want’ with a ladder reaching to the moon] – feared was the pollution of an English Eden by the ‘dark satanic mills’) with the great reversals to emancipatory progress which had looked imminent (Keir’s progressive optimism re the ‘diffusion of a general knowledge … [a] characteristic feature of the present age’ contrasting with the anti-intellectualism of Burke, who saw science as ‘smeared with blood … arrogant and uncaring’) resulting, at more prosaic levels, in setbacks to British liberal reform.

And all of this occurs at a specific moment, at a time when the gentleman amateur was perhaps more common as a leader in science than the professional or academic, and when events in Europe would have immense impact here in the British Isles, both strengthening our own imperial position – although it looked terribly insecure at the time, as America fought for and won its independence, causing the axis of our power base to shift from west (America and the west-indies) to East (India and the East-Indies) – and setting back the course of reforming liberal politics at home by many decades. All of which developments continue to inform our culture life even now. From our pride in Darwin to our troubled and alienated relationship with Europe. Re-posting this post-Brexit this aspect seems even more poignant. .

Many of those in this story were also proto-capitalists, as well as industrialists, making and sometimes losing fortunes, speculating with their investments. Erasmus Darwin had to earn his own living, as a doctor. His desire to publish much of his scientific work anonymously, and disguised as poetry, was influenced by a need to secure his reputation and private practice. His involvement as an investor in canal building, speeding the pulse of British industrialisation in a manner akin to the effect steam engines would shortly redouble, was what ultimately meant that Charles Darwin could work on evolution as a gentleman of leisure. Fascinating!

Vast in size and coverage – so big – like Erasmus at his dinner table (which had to be modified with a semi-circular cutaway), I couldn’t always fit it into my reading rest – this is a very interesting, informative and enjoyable book. Whilst I kind of wish it had been a bit leaner, given how much Uglow covers it’s understandable that it should be a bit of a mammoth.