This was the sole new book purchase, of my recent trip to Topping Books, Ely. I bought two very cheap books that same day, from Oxfam. One on Caravaggio, the other, A Tolkien Bestiary. The Caravaggio one is for cutting up and framing prints. The Bestiary was a book I had as a child. Something for old times sake!

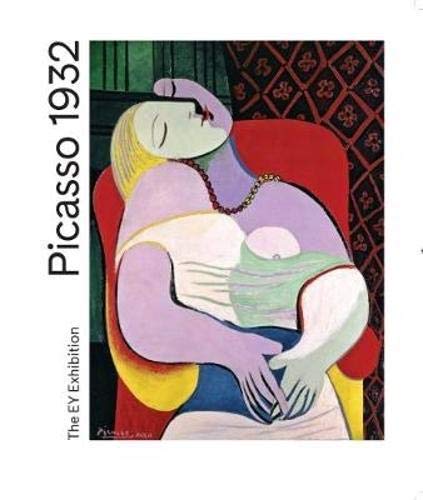

Picasso 1932, was an entirely new thing to me. I hadn’t even been aware of the recent-ish Tate exhibition, of which it is a catalogue/accompanying monograph. I’m a massive Picasso nut. I just love his prodigious output; the rampant fecundity and diversity of it all. The single year theme is great. It really accentuates Picasso’s incredible creative energies. The quantity, variety and quality of his work is, I find, always astonishing. It’s kind of like he’s a conduit for continent-shifting levels of energy, a continually erupting vent of Krakatoan proportions.

Picasso often talked about making art like a child. And here he talks about painting ‘arses’ (got to love his earthiness!) like a blind man; painting it as it feels to the touch. How delicious! The Mirror, pictured below, achieves just this, I reckon. And rather cheekily, I might add. It’s even as if the lady’s ‘pillow of clouds’ type backside is actually a dream object, in a cartoon-style thought bubble. Which of course it is.

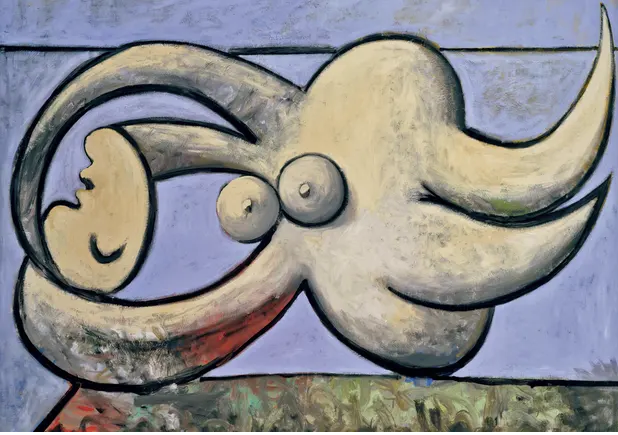

The above pictured Reclining Nude has a soft spot (or two, or three…) in my heart, as it’s a painting I bought as a picture postcard on a visit to the Musee Picasso, in Paris, many, many moons ago. And I love how speaking of moons, he uses crescents of white repeatedly. And the use of apple-esque red and green, also, is delicious.

Briefly returning to the theme of arseholes, as well as this cataloguing the Tate Modern exhibition (2018), it also covers and celebrates Picasso’s first career retrospective, of 1932, around the time he was turning 50. I’m 49 now, so this is very resonant for me.

Rather ironically, one of Picasso’s exhibitors, Paul Rosenberg, is quoted in here as saying ‘I refuse to have any arseholes in my gallery’. I love art and artists. But many – and it’s often been said of Picasso – are, frankly, the very epitome of assholes. And gallery owners and art critics? Even worse!

How ironic that Rosenberg would object to hanging arseholes on his walls, but could be very tolerant of the same populating the environment of his gallery!

One of the many, many, many things I love so deeply about Picasso is how varied and prolific his work was. Have I said this before? I’ll say it again; one of the many things I love about Picasso is how much work he did and how diverse that work was.

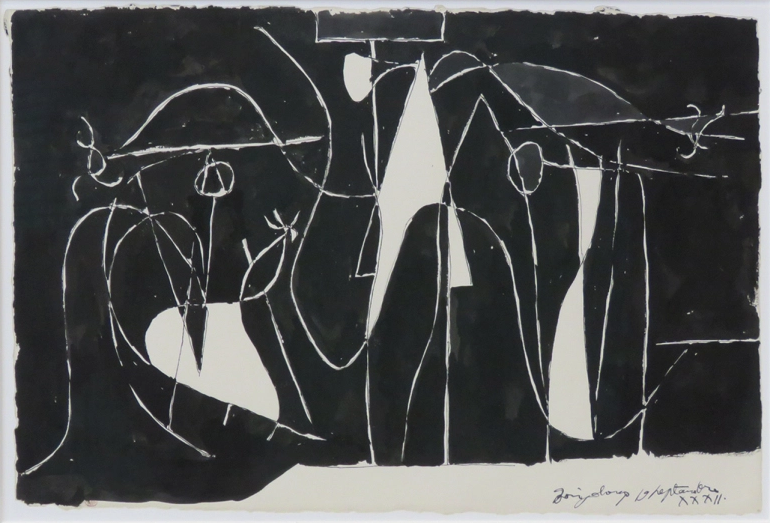

In this year/book alone, he ranges from monochromatic drawings and paintings to orgies of colour, soft round pillows and hard sharp angles, and then there’s the sculpture. Sometimes the links between periods, styles or themes are clear, whilst at others he jumps around like a grasshopper on PCP.

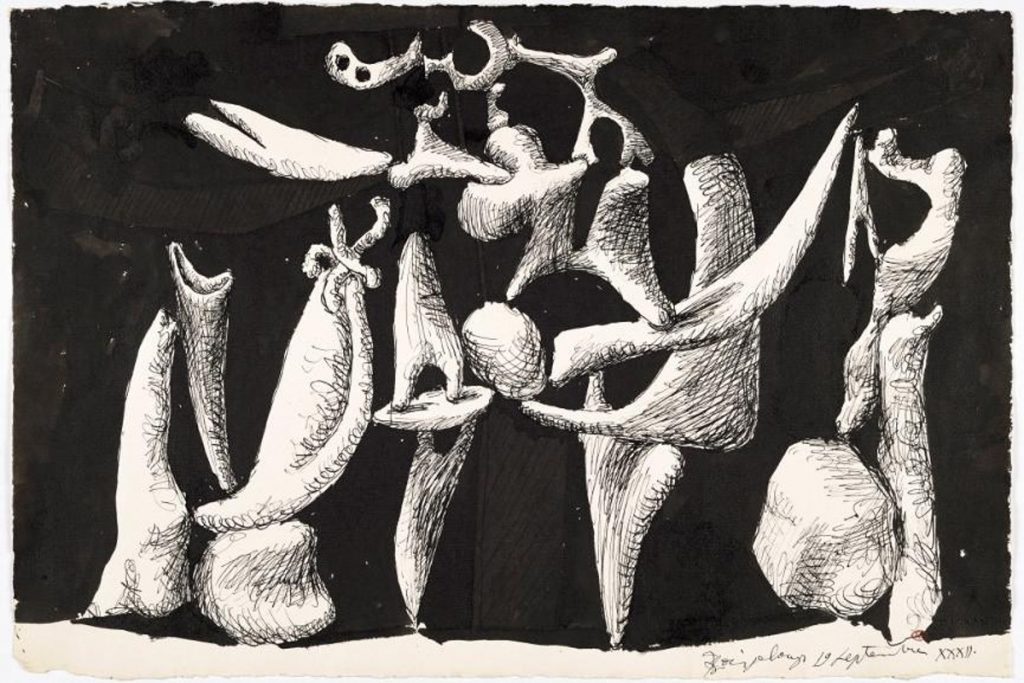

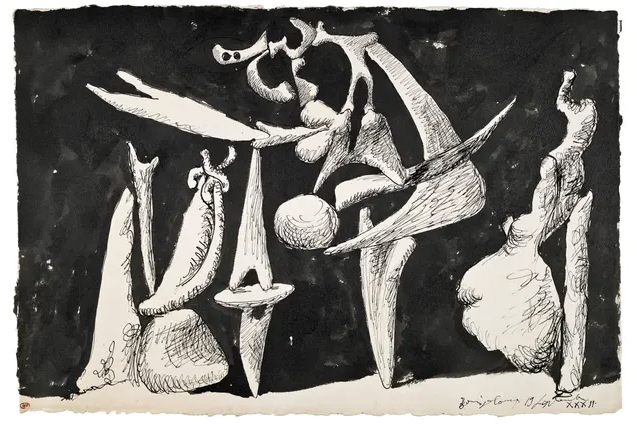

And very often he works through ideas in series of closely related works. Riffing away (appropriately enough he often riffs on guitars/flutes, etc*), looking for perfection, or that elusive magical alchemical quality great art can have. As he puts it: ‘ I can rarely keep myself from redoing a thing… after all, why work otherwise, if not to better express the same thing? You must always seek perfection.’

Ironically, for one of the greatest artists of all time, he is incredibly unlike most appallingly hip artsy types, whose preciousness often manifests in a combination of spiky arrogant feeling obscurantism, and an almost monomaniac visual aesthetic.

The series of crucifixions above illuminates several of these ideas; his playfulness, the stark stylistic contrast between this stuff and his colourful cream-puff nudes, and how he sought perfect through re-iteration.

That said, Picasso’s own spoken words – at least as communicated in books such as this – range from the refreshingly earthy and unpretentious (I like his statement about not making art ‘serving the interests of the political, religious or military art of any country.’) to the painfully self-consciously intellectual or opaque: ‘I will never fit in with the followers of the prophets of Nietzsche’s superman.’

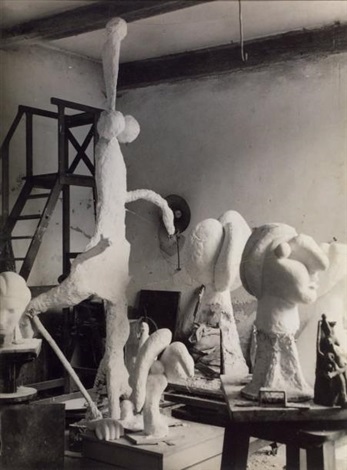

As well as the series of related artworks, some on themes such as seated ladies, female nudes, bathers, crucifixions, Bacchanalian scenes, etc, there are whole sketchbooks, reproduced here, as well as photo-articles such as Andre Breton’s Brassaï illustrated piece on Picasso’s sculptural work at Boisgeloup.

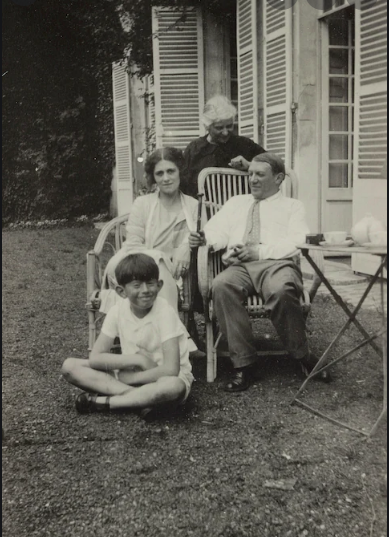

And, rather nicely, the importance of places, as well as people, is really addressed nicely in this book, via maps, black and white photos, and text.

This review is primarily my initial response to the visual content of this terrific book. Most of my interest in art books lies in simply looking at the artworks, and other images. Art history texts are infamous for all too often being tortuously verbose and pretentious. What little I’ve read here, thus far, seems alright.

But the real treasures here are not the words, obviously, but the artworks. And for these alone, this book is, for me, essential. Love it!