Capping a fabulous run of albums that featured a fairly stable team of jazzers, whilst this isn’t the final instalment of Waits’ love affair with his jazzy Tin Pan Alley persona (that was to come in the form of the album that is both the sound track to a Coppola movie, and a standalone masterpiece – One From The Heart – which was itself inspired by a track from this album) it was the last in a consecutive string of releases built around the relatively stable team of bassist Jim Hughart and the incomparable Shelly Manne, on drums. Whilst Howe and Alcivar remained in the Waits orbit for a little longer, Hughart and Manne would only make the one return (for the aforementioned ‘One From The Heart’), so this is really the document of the end of an era in the Waits story, the next chapter destined to be more raw, bluesy and electric, with albums like Blue Valentines and Heartattack And Vine .

As well as ending an era of collaboration, it also finds Waits’ partnership with arranger Bob Alcivar hitting a kind of cinematic peak (again, a style to be notably if somewhat differently reprised on ‘One From The Heart’). Indeed, the liner notes describe the recording as “A Mr Bones Production / Tom waits: Piano & Vocals / Co-Starring Bette Midler / With this great supporting cast … [and then lists the band]”. The album begins with a beautiful little programmatic opener, ‘Cinny’s Waltz’, in which Alcivar’s lush but minimal arrangement turns a very small musical nugget from Waits into a beautifully evocative vignette, leading in turn into the absolutely gorgeous melancholy piano ballad ‘Muriel’. Trumpeter Jack Sheldon takes the lead at the end of ‘Cinny’s Waltz’, and his breathy tone is perfect, sax player Frank Vicari picking up the muscial baton for ‘Muriel’, with an equally soft, breathy tone.

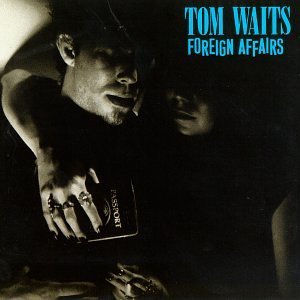

Track three, a duet with Bette Midler called ‘I Never Talk To Strangers’ (in the liner notes Waits enthuses ‘Bette, your absolutely colossal’!) is the very track that inspired Coppola (who apparently discovered Waits through his sons enthusiasm for him) to craft a whole film around the musical moods that Waits generated. I actually think the pairing of Crystal Gayle and Waits, for OFTH, is actually more musically successful than this number, which is nonetheless both very good and very endearing. It’s worth mentioning at this point the brilliant back and white photography of George Hurrell, which adorns the record, adding an expressionistic noir vibe to it’s filmic associations. In some of these pics Waits is the epitome of studied cool, but there’s one absolutely priceless shot, in which he looks almost freakish, head cocked back, eyes-closed, a half-smoked ciggy mid-mouth, and a hairy chest peeking through the skid-row suit. But that’s the thing: Waits probably chose that pic himself, showing he’s the compete deal, a kind of surreal lounge singer, his spidery double jointed fingers bent back, and his oily/greased shaggy coiffure a riot of curls that almost seems to express his inner wildness.

‘Jack And Neal’ is another celebration of things ‘beat’, literally telling a tale of Kerouac and Cassady on the road, with all the accoutrements, Mexicans, girls, benzedrine, jazz and booze. This is followed by the boozy bar room lullaby to old friends long missed, ‘Sight For Sore Eyes’, and that wrapped up side one, in vinyl days of yore. You’d then flip the platter, and get the ultra-cinematic ‘Potter’s Field’. Like ‘Jack & Neal’ this is in essence a recitative rap, a spoken word piece. But whereas the latter becomes a funky slinky double-bass lead jazz number, heavy on rambunctious rhythm, ‘Potter’s Field’, still snaking across sinuous upright bass, is an altogether moodier affair, with spooky sounds from the orchestra. Here it’s worth pausing to note just how stupendously brilliant these recordings are: this was all laid down direct to two track. That’s right, live, in one take, with the whole orchestra! The excellent music technology magazine Sound On Sound ran a feature on ‘Bones’ Howe in which he discussed their working methods. Essentially they went for the purest simplest, most ‘real’ approach. None of this ‘we’ll fix it in the mix’ nonsense that the digital age has made so ubiquitous (and on which, I must confess, I’m very dependent).

Next up comes the beyond-words-brilliance of ‘Burma Shave’, a number that had evolved from a spoken word piece. If you ever get the chance to see Waits’ Austin City Limits performance (a superb film of a brilliant concert, one of the best I’ve ever seen, that really should be made commercially available, preferably remastered and in high-definition) from around this time you’ll hear the song in development, when it was recited over a cycle round the first four chords of ‘Summertime’, brilliant in it’s own way, but not as fabulous as the fully realised album version. Jobim’s wonderful ‘Agua De Marcos’ is an example of sublime poetry set to simple cyclical music, very different but equally magical, and I think Waits lyrics frequently have a similarly high level of poetic richness and density that makes them almost synaesthetic. I believe some have called this Waits most underrated album, and, as I write this, listening to the album, I’m incline to agree. It’s chock-full of jaw-dropping brilliance… pure magic.

‘Barber Shop’ turns Waits lyrical talents in a more humorous kaleidoscopic direction, and is a close cousin to ‘Jack & Neal’ musically, with double bass and drums dominating the music, grooving funkily, Shelly Manne’s beautifully subtle nuanced touch on the drums particularly worthy of note. And finally Tom gets his ticket and sails off on the title-track ‘Foreign Affair’, a slice of louche sophistication, with very rich jazzy chordal voicings, and a sensibility that mixes the best of Tin Pan Alley with an almost European Cabaret-esque vibe, particularly when what sounds like an accordion joins in towards the end. Totally brilliant, this might in fact be one of Waits most consistently top-notch records. And given how good his catalogue is, that’s really saying something.