![]()

As I mentioned in the post on my recent birthday, one of several books I recently acquired is Inside The Third Reich, which I’m currently reading.

Written during his incarceration in Spandau, it’s interesting to a military history buff like me how little Albert Speer has to say about the military campaigns in Poland, the Low Countries and France, compared with the great detail he goes into about his architectural projects.

Indeed, although he’s a favoured member of Hitler’s innermost coterie, it’s clear that in the lead up to and the early stages of WWII Speer is very definitely on the outside of Hitler’s military circles. This would change, when he became armaments minister. But at the point I’m at, Speer is at pains to stress that whilst he himself felt such monumental projects as Hitler’s plans for central Berlin should be put on hold, in order to focus exclusively on the war effort, The Führer himself insisted that this non-essential work be carried on regardless.

For such immoderately grandiose plans to have ended up having such fleeting and ephemeral existences is in itself a fascinating and tantalising thing. Many of the buildings Speer worked on remain realised only as drawings or, at best, models. The latter only surviving the war (as far as I know) in photographs.

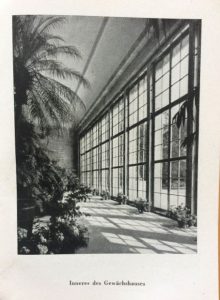

A bit of googling turned up a few things, such as a recent book on Speer’s architectural work, a short article about a ‘lost’ interview with Speer by Robert Hughes, and a number of instances of people selling a photo-book on Speer’s Neue Reichskanzlei (New Reich Chancellory), pictures from which help illustrate this post.

Speer also has a decidedly rueful note in his hindsight view, suggesting more than once that the aphrodisiac of power caused his style to develop in ways he suggests we’re not ‘true’ to his real nature. Perhaps the image above hints at the lighter more modernist approach he might’ve pursued more, had he not become court architect to a megalomaniac powermonger?

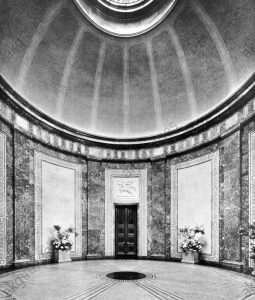

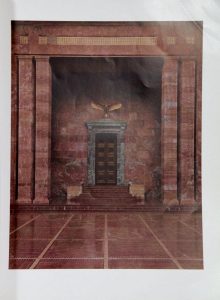

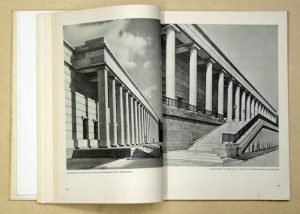

Speer also says he developed a ‘theory of ruins’, and that he discussed this with Hitler, and the two of them were in agreement on it. The idea was, in essence, that buildings of the Third Reich should be built in such a way that, like the ruins of ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, they would still be awe-inspiring a thousand or more years hence.

The irony was to be that destruction would be visited upon the architectural works of Speer and Hitler’s other architects far sooner. And so it was that Speer’s new Reich Chancellory looked as you see it above, not in 2943, but just two years after completion, in 1945.

NOTES:

[1] Breker clearly captures Speer’s likeness very well, but his Mekon like bulbous bonce, probably intended to flatter Speer by reflecting/emphasising his intellectual aspect, does look a bit comic now.

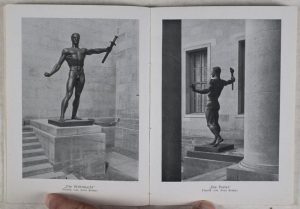

[2] The horse – possibly Breker again? – has a very stiff, heavy, unnatural look, typical of Nazi approved sculpture. The two figures pictured above also have this rather leaden feel.

[3] Revisiting the ruins of one of his mammoth projects with Robert Hughes, years after the war and his release from prison, Speer confessed that it could now be seen that the outward show of pomp and gravitas was only skin deep, and that even the quality of much of the stone cladding, which covered the concrete bulk of the buildings, would’ve disappointed his beloved Führer.

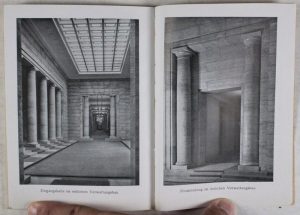

One of Hitler’s primary aims in the new Reich Chancellory was to overawe visiting bigwigs, and make them feel both small and tired. The first could be accomplished by architecture on a huge scale, the second by making them walk miles of hard shiny corridors before they met him, cowed and exhausted. Speer himself notes, in retrospect, that all of this, and even his own design style, as it evolved, becomes – indeed is intended to be – inherently oppressive. Well, that’s fascism for you in a nutshell!