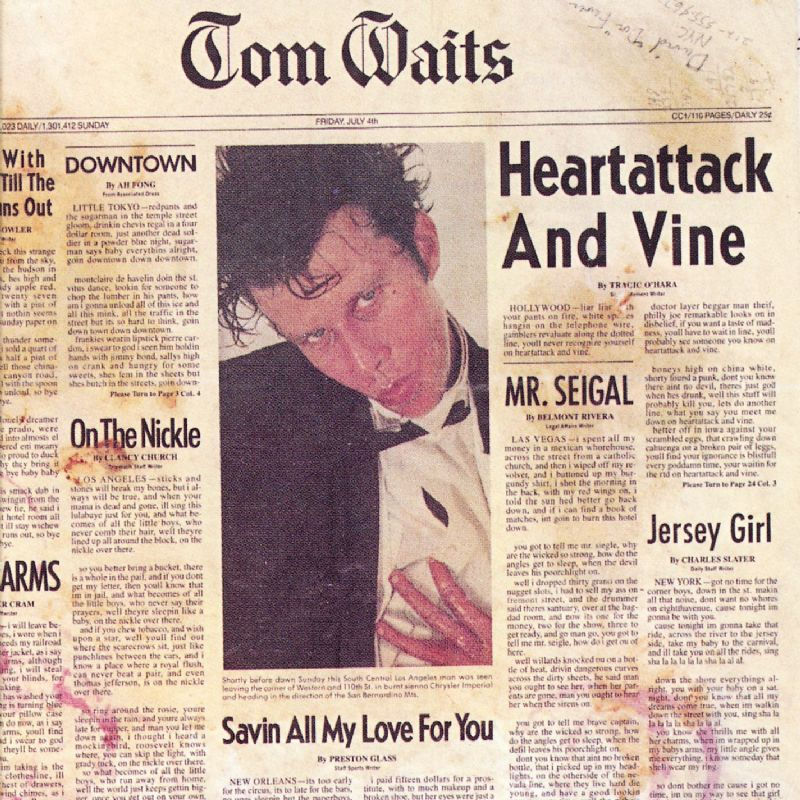

A bit of a bi-polar, Janus-faced album this, the last on Herb Cohen’s Asylum label from the genius that is Tom Waits.

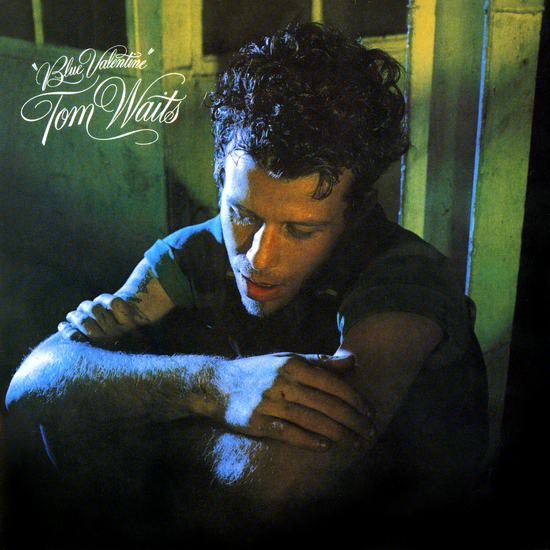

After a run of classic albums largely made with a steady team of collaborators (put together on the whole by producer ‘Bones’ Howe, who’s still manning the mixing-desk here), Waits had released the more gritty, urban, electric, and r’n’b based Blue Valentine in 1978. Two years later he entered the studio again for an even grittier set of sessions, but with a more cohesive line up, featuring Harold Bautista on guitar, Ronnie Barron on keys, Larry Taylor on bass, and ‘Big John’ Thomassie on drums. Some of these guys were also touring with Waits around this period: Barron and Thomassie were natives of New Orleans, Taylor famously played with Canned heat, and Bautista with Earth Wind and Fire. Howe, bassist Jim Hughart, and arrangers Jerry Yester and Bob Alcivar all survive from previous scenarios, providing an element of continuity in personnel as well as musical flavours. This album is also the first time bassist Greg Cohen appears on record with Waits. He would become a frequent Waits collaborator over the next decade or two

The music is roughly divided between the gritty urban-sounding electric blues material, and some heart-achingly beautiful ballads. The former consist of Heart Attack & Vine, the slightly unusual bar-band instrumental In Shades, Downtown, ‘Til The Money Runs Out, and Mr Siegal. And all, save In Shades, are soused in tales of sex, drugs, and criminal low-life, with a real whiff of Last Exit to Brooklyn , a world populated by semi-mythical hookers and hoodlums. ‘How do the angels get to sleep when the Devil leaves his porchlight on?’ Waits wonders on Mr Siegal. Think The Beats at their seamiest: Herbert Huncke, ‘Bill’ Burroughs ‘rolling’ drunks on the subway. An American demi-monde, such as produced the real life sex/crime scenario behind the Kerouac and Burroughs collaboration And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks .

The first of the ballads is the beautifully sentimental Saving All My love For You, which starts with ringing bells. Then, after the gravelly Downtown comes the beautiful guitar-based Jersey Girl (famously covered by Bruce Springsteen), which features a fabulous slow-building orchestral arrangement by Yester. On The Nickel was apparently either written for, or used at least in a film of the same name, about a Skid Row alcoholic, and is a real gem, Waits’ boho-hobo poetry seamlessly stitched together with his most sentimental side, and once again benefitting from a tremendous orchestral arrangement (this time by Bob Alcivar, whose work on Waits’ One From The Heart recording is pure magic)… wonderful! Yester picks up the baton for the final fabulous ballad, Ruby’s Arms… Oh God, how I love Tom Waits when he’s at his most sentimental. This is such a great track!

All in all, a brilliant album, and slightly strange, in that his two tendencies – the two sides to his muse that his wife Kathleen Brennan has called ‘grim reapers’ and ‘grand weepers’ – can already be seen to be polarising and diverging ever more clearly. In my view, everything he did up till Swordfishtrombones (perhaps even including Rain Dogs and Frank’s Wild Years), including this terrific LP, is absolutely 100% essential.