Helping put anomalous monotheism in its proper historical context.

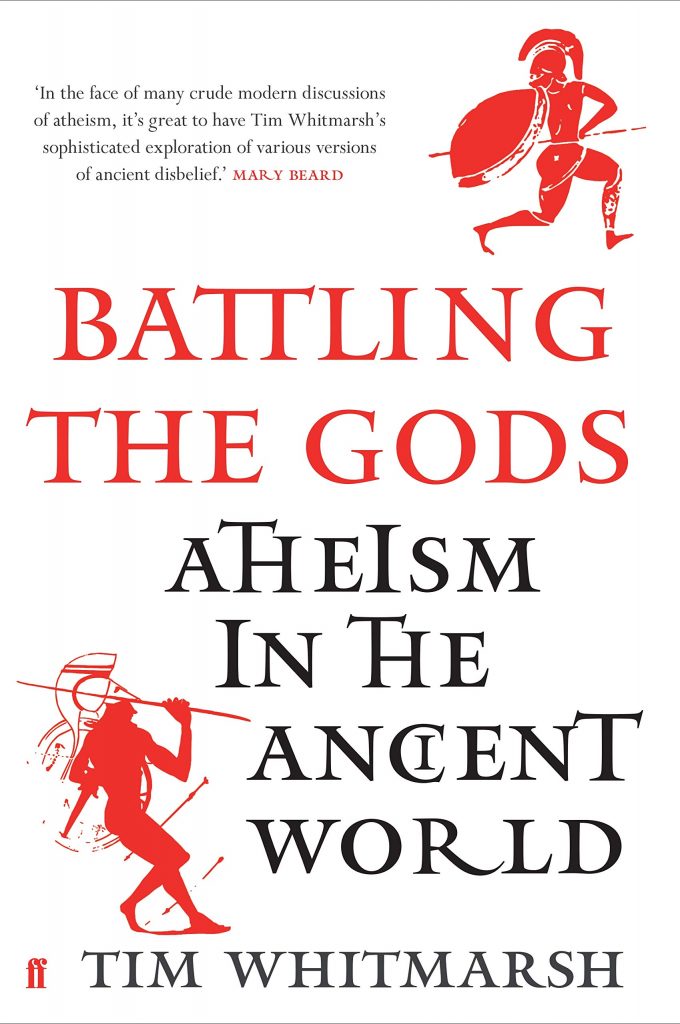

In Battling The Gods Tim Whitmarsh performs some fascinating cultural archaeology, digging up and reconstructing some of the deep history of naturalist (as opposed to supernaturalist) thinking.

There are two things about the way he deals with this subject that disappoint me a little: first, the acceptance of negative terms – his subtitle, Atheism in the Ancient World, uses the primary one – which have been thrust upon those who question religion and superstition (I nearly said ‘the deep history of disbelief’ above, which sounds snappier perhaps, but is once again a negative); and second, limiting the book to the ‘classical’ world/era.

But to be honest these are, for me, very minor gripes. The first issue arises from the fact that even two or three centuries after the Enlightenment we are still emerging (or so I fervently hope) from the religious hegemony of a Christian past, and simply accepts, more or less, the common parlance of the status quo (although to his credit and my delight Whitmarsh frequently challenges this negative framing and its causal religious bias). And the second limits a potentially massive and difficult subject to a smaller more manageable project, resulting in a wonderfully focussed and readable book.

Ever since my own ditching of religion, I’ve harboured a suspicion that the historical narrative left by a Christian dominion of close to two millennia has hidden a much more complex, diverse reality, in which alternative views, from persisting ‘paganism’ to outright disbelief survived, and were far more prevalent than surviving Christian history would have us believe. Whilst Whitmarsh doesn’t address this within the period of Christian dominance (indeed, he says ‘The arrival of Catholic Christianity – Christianity conjoined with imperial power – meant the end of ancient atheism in the West.’), he does make a very convincing case that ‘viewed from the longer perspective of ancient history, what is anomalous is [not post-Enlightenment atheism, but] the global dominance of monotheistic religions and the resultant inability to acknowledge the existence of disbelievers.’

This book primarily looks at the Greeks, even when it deals with the Roman era, and we meet some fascinating characters, from the familiar, like Socrates, Plato, Diogenes, the Epicureans and Stoics, etc, to the less well known. One of my favourite discoveries in respect of the latter category was a chap called, rather ironically, Demonax, whose position Whitmarsh describes thus: ‘aggressively satirical, an enemy of dogma rather than a doctrinaire adherent to any particular philosophical code.’ Sounds like a topping kind of chap to me, eh what!?

One of the key points that emerges is that, just as human social and political organisation evolved from small tribal units to city states to empire, so did the roles and functions of religion. The loose, adaptive, and, broadly speaking, more tolerant/pluralist mode of polytheism eventually gave way to the adoption of a monotheistic faith, embraced by Roman imperial power – thanks a bunch, Constantine! – in a marriage of political convenience. Whitmarsh eloquently and succinctly sums this seismic shift as follows: ‘the real ideological revolution engendered by the Christianisation of the empire [was] the alliance between absolute power and religious absolutism.’

I really enjoyed this book. I would love to read more on the same theme, concerning similar naturalist free-thinking in other places and times. Even, dare I suggest, during the heyday of European Christianity, a period when we lived under a new and less tolerant dispensation, and from which we are only now gradually emerging.

PS – This is another archival review; I read and reviewed the book in 2016. I even went to Heffers bookshop on Trinity Street, Cambridge, around the same time, and attended an author’s talk by Whitmarsh, which was great.