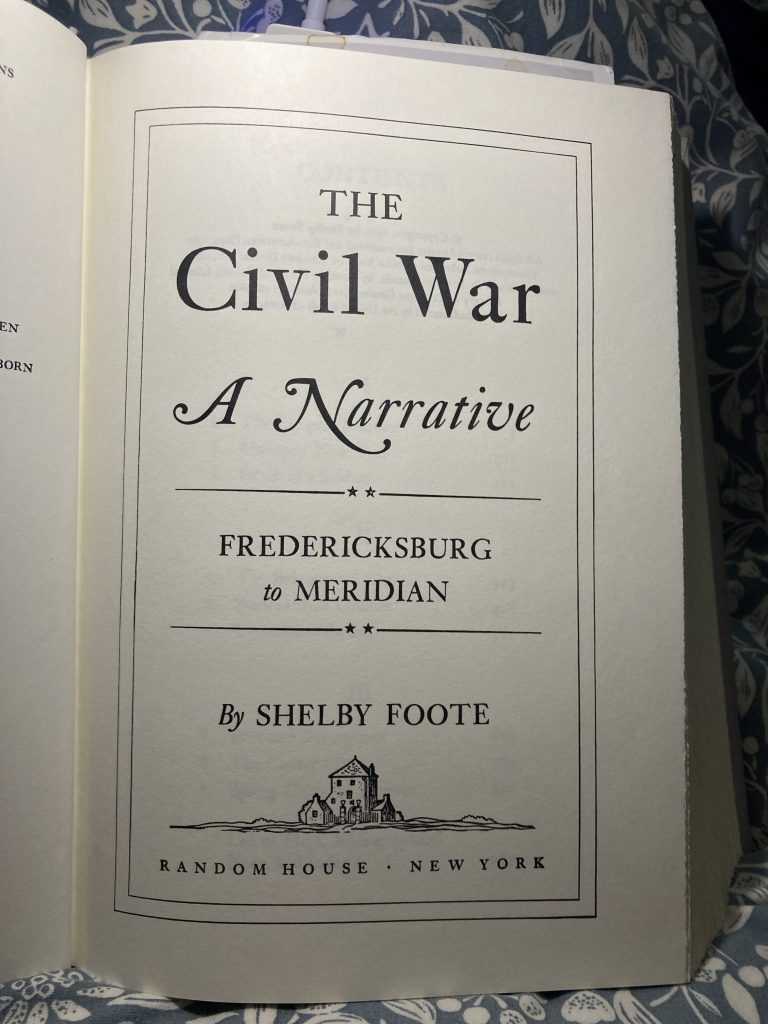

I just finished the mammoth fifth chapter; Stars In Their Courses, 154 pages – the size of a small paperback novel – on the battle of Gettysburg.

Marking, more or less, the middle of the trilogy, and, more or less, the middle of the war, it’s a kind of midway hinge of the whole story, and marks the beginning of the end for Lee and Johnny Reb.

I often write about how much I love many short chapters. It’s nice to chomp steadily and quickly through bite-sized morsels. Mammoth chapters can feel like a real slog, sometimes.

Not so here, however. Within the chapters there are little mini-breaks. And I treated these like mini-chapter-ettes. I have the Gettysburg movie on DVD, and that’s a two-disc affair. That left me thinking it was a two day battle (it’s a while since I watched that!).

But it was three days, and there were also peripheral actions. And all of this is covered admirably here. Indeed, to all intents and porpoises, this chapter really is a mini-novel. Highly enjoyable!

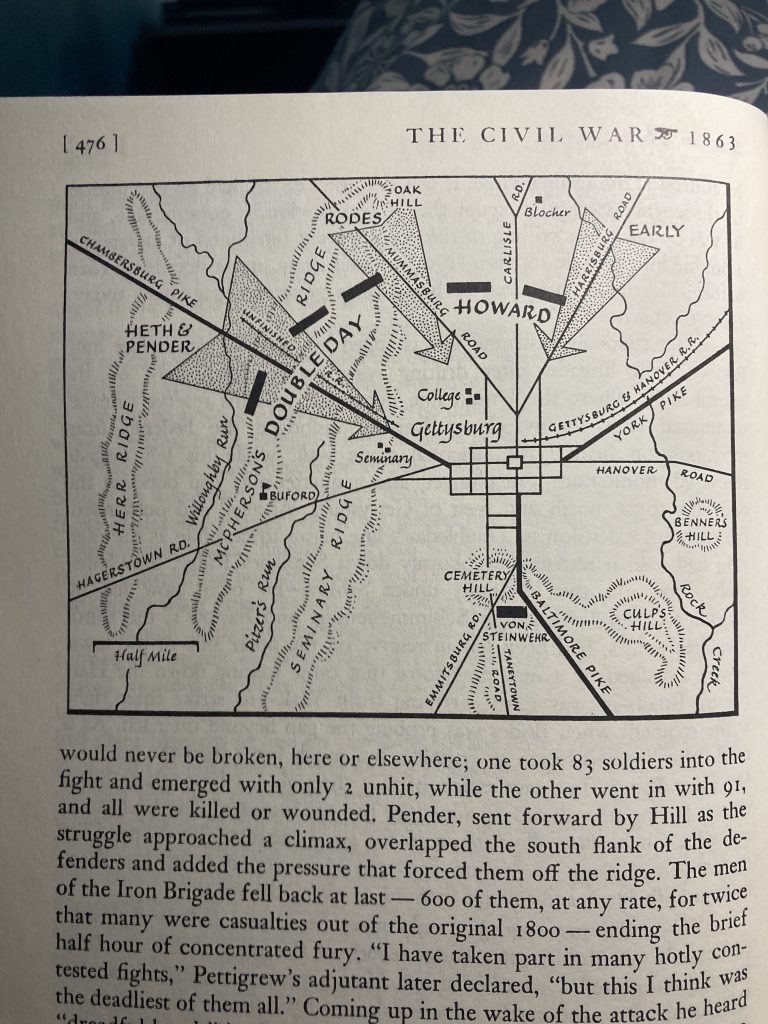

The battle itself, with Lee missing his eyes (Jeb Stuart’s cavalry), and Meade forced to fight on ground other than that he’d chosen and preferred, was therefore an instance of two generals having to deal with fighting under less than ideal ad hoc conditions.

Lee’s formerly successful hands off m.o. seems clumsily mistaken here, and comes undone. Whereas Meade’s typical and predictable Union caution, so often their undoing, in this instance seems both correct, and pays off.

This very bloody battle becomes the first significant clear cut Union victory in a long while, and a turning point – albeit a predictable enough one (re the overall arc of the war, that is, rather than the individual battle) – in the war.

Shelby Foote’s enthusiasm is contagious. And his writing style, informed no doubt (in a Stateside echo of British novelist R. F. Delderfield’s Napoleonic passions) by his authorial skills.

Fabulous! Very highly recommended.

PS – The title sounds Shakespearean, but is, according to my brief look online, Biblical, coming from the King James’ Judges, 5:20, and, very aptly, referring to the fortunes of war:

They fought from heaven; the stars in their courses fought against Sisera.