I was left wondering about Debbie Reynolds, which lead me to this interesting bit of tittle tattle…

renaissance man

I was left wondering about Debbie Reynolds, which lead me to this interesting bit of tittle tattle…

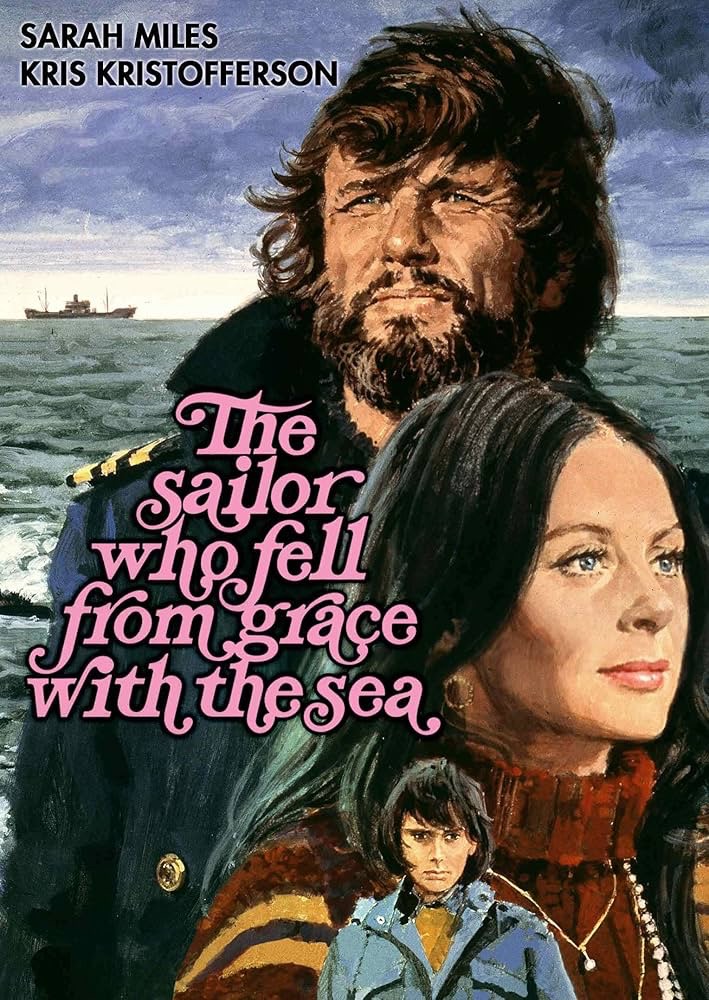

Wow! A pretty bonkers film, this. Part Mills & Boon Romance, part seventies softcore, and part psychological horror.

It’s superbly shot, acted, directed, and so on. In many ways, certainly visually, and occasionally sonically, it’s very beautiful.

But there’s also a rather horrid rotten core to it as well. This mainly emanates from an awful lil’ Hitler type character, called Chief.

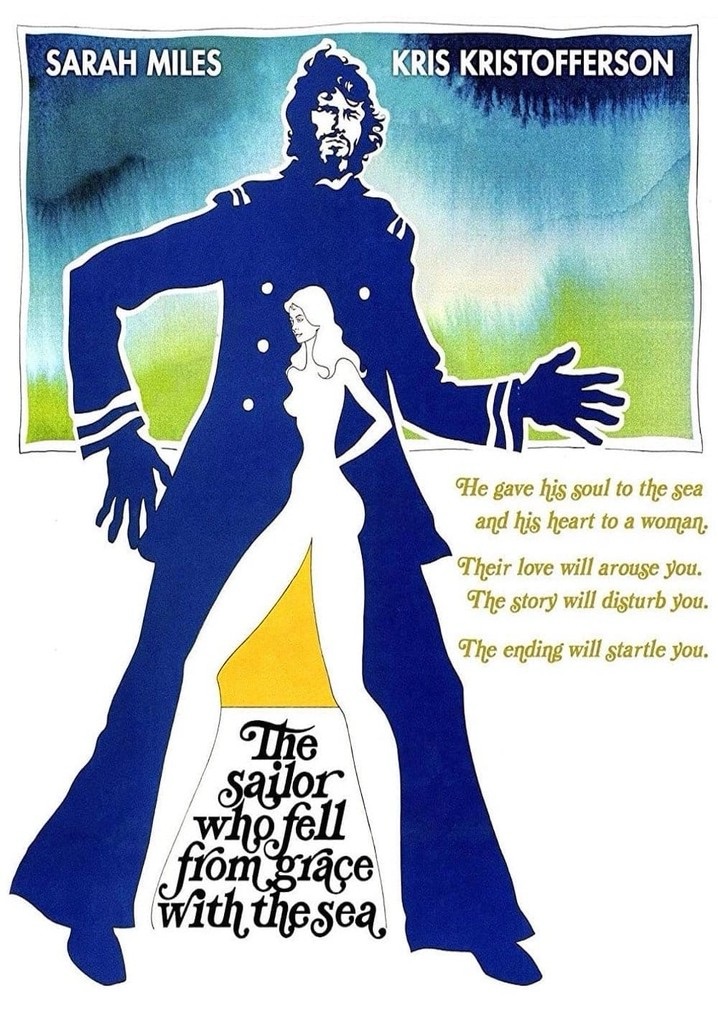

For now I’m going to leave my ‘review’ pretty basic. I’ve long wanted to watch this film, as: I’ve always loved the poster; I quite like Kris Kristoffersen, in the ‘70s; and Sarah Miles is gorgeous!

There were parts of this film I could barely watch. Two parts. One involves the Chief dispatching the family cat, involving his hapless henchmen in the heinous act.

*Can’t see many films nowadays going places like this! And certainly not in the manner of this ‘handling’.

The other? Well, I basically bailed on the film. Not ‘cause I think it’s bad. But because it was getting too dark for me, as I am these days. I need light, warmth, happiness!

Would I recommend watching this film? That’s a tough one, to be honest. But I’m glad there are films like this out there. Because it’s not your average humdrum pulp potboiler.

I think it’s a film I might come back to? But then I might not? Who knows? Who cares…

I certainly want to find out two things arising from watching it: what font they’ve used in the titles, and on the posters. And who designed the superb Avco Embassy ident that we see at the beginning.

I watched the film on YouTube. And I see that it’s also been made available to download, here.

I only really knew Sarah Miles as a dotty aristo’ type, from an episode of Suchet’s Poirot. It’s kind of odd, alarming, and yet very erotic, seeing her as she appears here.

But here, nothing is merely surface appearances; the theme of her son spying on her lovemaking complicates what could’ve been straightforward eroticism.

In an intriguing footnote, Earl Rhodes, who plays the utterly loathsome Chief, continued acting for a while, before switching to being a cameraman. Later on he became involved with the Falun Gong martial arts/religious movement. This latter activity saw him deported from China, back to the UK, in 2002.

FOOTNOTE:

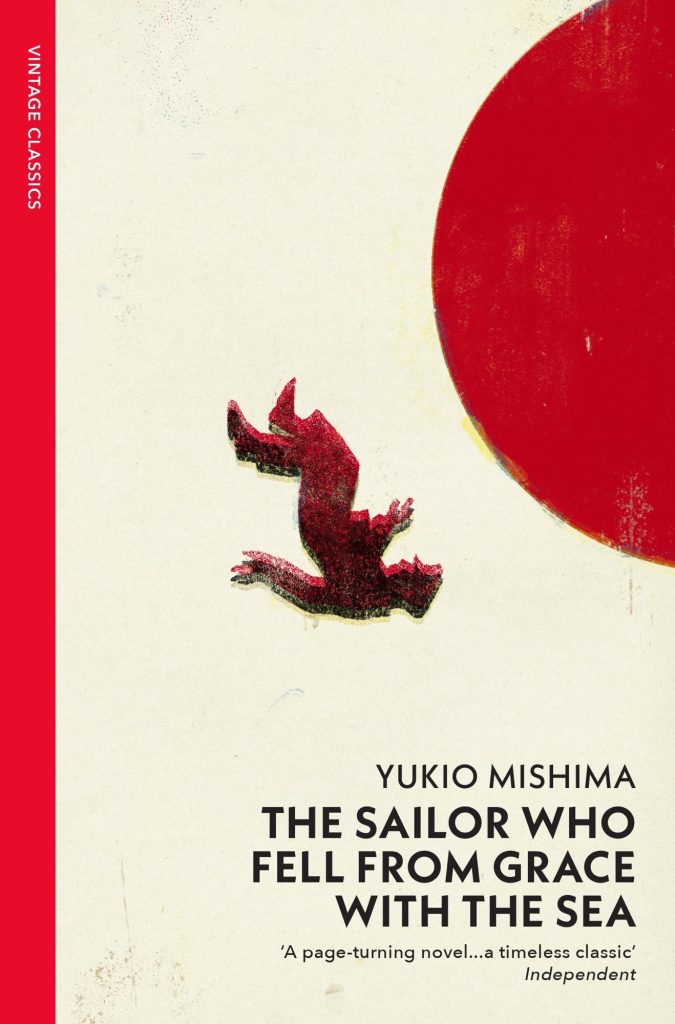

This film is based upon, or at least shares a title with, a book by notorious Japanese novelist Mishima. From what little I’ve read about him, he was a right wing nut job. So it’s possible that in his book the Chief type character is the hero. Whereas in this film I’d say he’s certainly not. But it’s all very interesting. Mishima committed seppuku, ritual self-disemboweling, after staging a failed ‘nationalist’ coup!

I just put on a film, The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea, and I absolutely adore the Avco Embassy logo ‘ident’, with which it begins. I’ve tried to find out who designed it. Looks very Saul Bass, to my eyes.

Wow… design perfection.

I have yet to find out who created this terrific logo, or the brilliant animated version. But this post commemorates it, for me, for now.

It looks, from the video atop this post, like it was in this form from 1968-82.

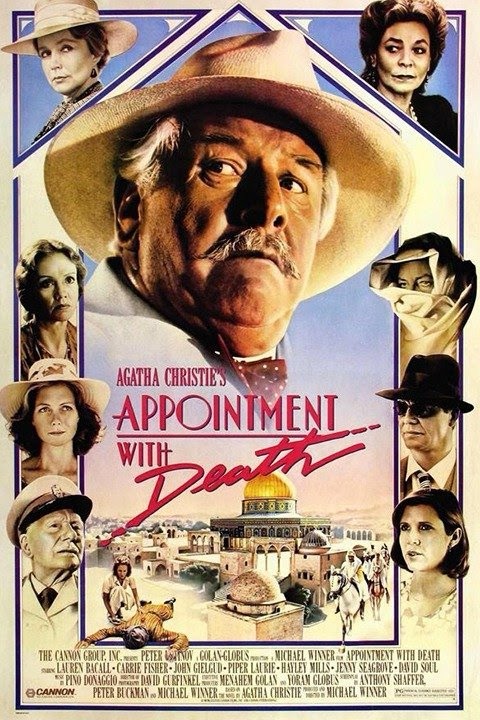

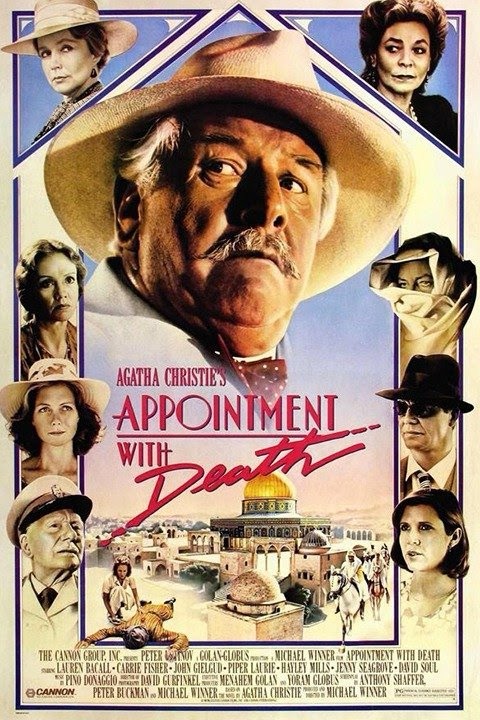

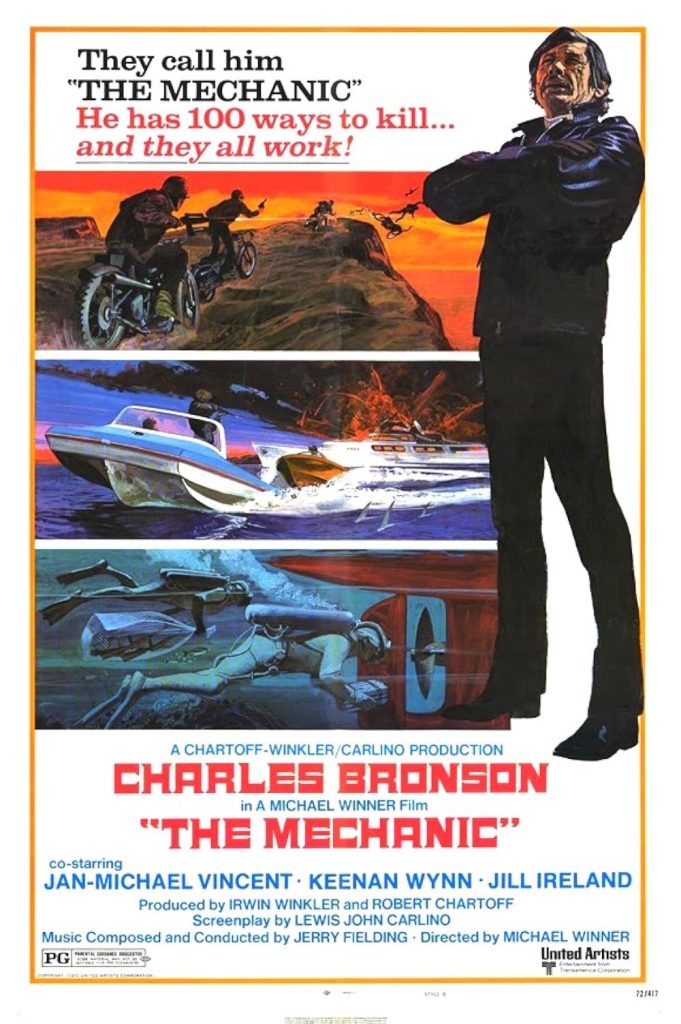

I watched this last night, New Year’s Eve. It’s not a Great Film, but it was a good fun watch.

Bronson plays Bishop, a professional hitman. He lives in ridiculous luxury, but is popping pills, clearly not a well man.

The opening sequence is great. About a quarter of an hour with no dialogue at all, just atmosphere and ‘action’, as Bishop goes about his deadly work.

It’s a morally ambivalent film, right from the outset. Bronson’s Bishop is clearly the ‘hero’, albeit in a dark antihero kind of way.

Having killed a seemingly harmless middle-aged man, alone in his homely bedsit, in a squalid part of town, Bishop’s next ‘job’ is a friend of his own (deceased) father.

Harry McKenna (KeenanWynn*) lives in even more ostentatious luxury than Bishop. Much good it’ll do him! He’s fallen foul of his ruthless bosses, and appeals to Bishop for help. Bishop meets with Harry, and as a result meets Steve McKenna, Harry’s wild playboy son.

*(?), from Dr Strangelove.

The stony faced emotionless Bishop’s next job turns out to be McKenna senior. He does his job with his usual meticulous preparation and attention to detail. In a way designed to make it look accidental.

His first victim will, we suppose, be deemed a victim of a domestic gas explosion. McKenna, a heart-attack.

Unaware Bishop killed his father, the younger McKenna stalks/grooms Bishop, with a view to becoming an assassin himself. This whole thread is rather weird, to be honest. Which I’ll come back to in a bit.

After playing cagey for a while, Bishop finally takes Steve under his wing. With disastrous results that unfold over the remainder of the movie.

Their first job as a team goes a bit awry. Let’s say it’s messy, and not according to plan. And whilst there’s only really one ‘mark’, two additional henchman are ‘offed’. Their bodies are dissolved in the acid baths of unwitting accomplices, an auto bodywork workshop.

Bishop is called in, and reprimanded for taking Steve on. He’s given a ‘cowboy’ job – a quick kill – that he doesn’t like (it’s not his usual m.o.), to put things right.

Rather strangely, they take their time and the ‘quick kill’ winds up being more elaborate than any of the others in the film. It’s also a double-cross/set-up. And not only that, Bishop and Steve have both been tasked with killing each other.

All of the above is, frankly, a series of elaborate Mcguffins, allowing the film to traverse a whole range of settings. From the urban squalor of the opening sequence, in L.A., to the luxury of several of the villain’s homes. From motorcycle chases in swanky L.A. to yachts in Italy.

There are also training segments, in which the film manages to shoehorn in some sequences that suggest the film is trying to be an action movie grab bag: assassin stuff, gadgets, martial-arts, etc.

My favourite of the exotic locations is Bishop’s pad. It’s amazing! Rather annoyingly, I can’t find any info’ in the place they used.

The acting is good. Not amazing. The roles, and the way it’s all delivered, are a bit dated/silly. There’s a hipster narcissism about Bishop and Steve, which would be pretty ugly even if they weren’t assassins.

I’ve read that originally Bishop and Steve were meant to be gay lovers. But that thread was dropped, when numerous mooted actors – e.g. George C. Scott – refused the lead role unless the homosexuality was taken out.

The Screenwriter for this film, John Lewis Carlino, called The Mechanic ‘one of the great disappointments of my life’, saying that what he’d written as a complex nuanced story was dumbed down from ‘a real investigation… into a pseudo James Bond film.’

The investigation? According to Carlino ‘a sort of existential statement on the license to kill and what is occurring in our society, how legalized murder is occurring through our institutions.’

Well, yes, there are hints at that. But ultimately this does rather wind up being a dumb, if stylish, celebration of a certain weird vision of what nowadays might be called a toxic masculinity.

The ending is properly bonkers. If also quite predictable. We’re lead to think that maybe these two are genuine buddies – if no longer allowed to actually be lovers! – after all, as they single, er… no, make that double-handedly dole out death to their mafioso overlords.

*Known to many as Stringfellow Hawke, from TV’s Airwolf.

But no, the cocky young Steve fulfils his contract on his former master and teacher, Bishop. Inheriting the Latter’s ridiculously cool pad. But wait… the wily Bishop strikes from beyond the grave! Ka-boom.

By this point, any attempts to explore the moral dimensions this film I doubt touched upon, are list, frankly, in a maelstrom of taciturn testosterone fuelled mayhem.

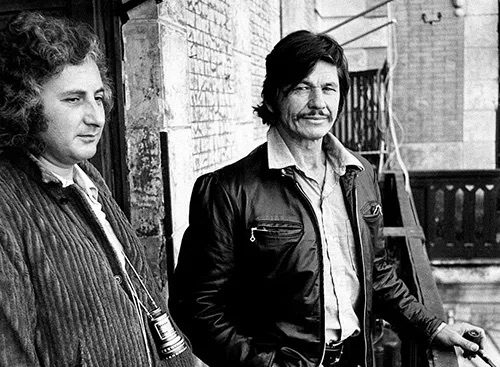

Despite all this craziness, I really enjoyed this film. It’s no classic. But it is fun. Bronson and Jan-Michael Vincent have real screen charisma. Michael Winner is a dab hand at getting an effective balance of mood and action.

The above photo was actually from the day before (30th Jan). Out delivering. Today I delivered around Stamford. Lots of beautiful villages. But I took no pics.

When I got home, Teresa had cooked a delicious meal. Plus we had tempura stuff, with dips, after. And some Nozecco, etc. to ‘toast’ the New Year.

I find myself in bed by 8 pm. Having played a little bit of Crash Bandicoot, and eaten a slice of Xmas cake. I’m dead tired. And have no desire to see in the NY.

As so often, I just want the sweet oblivion of sleep.

Freddie Hubbard Quintet plays a set on the PBS television show Every Tub On It’s Bottom. Nov’, 1977.

Lineup:

Freddie Hubbard, trumpet

Rick Zunigar, guitar

Larry Klein, bass

David Garfield, keys

Carlos Vega, drums

I came across this footage whilst looking for example of Carlos Vega’s drumming outside of his work with James Taylor. I’m guessing the Larry Klein on bass is the same dude who eventually shacked up with Joni!?

I’m trying to grow sideburns, or mutton-chops. Also known as ‘bugger grips’! Is this wise, I wonder? Well… who cares, eh?

We’re thinking of spending a simple quiet day at home, today. Resting and reading. Although I’ll have to go to work. Got one shift booked already. Ideally I need to do another, as well.

Wow! This is really terrific.

This a one of the best programmes I’ve seen in recent times. A proper slice of old school BBC factual television that educates, inspires, and uplifts. How Reithian is that!?

The bulk of the programme, is given over to us epic journey by Bactrian camel, across the Gobi Desert.

The last 5-10 minutes culminates in both Buchanan’s 52nd birthday, and his encounter with the elusive and very rare Gobi Bear.

This has many levels of resonance for me: I am 52, soon to turn 53 (in just a few days!), and as a child I had a toy bear, that just so happened to be called… Gobby Bear!

Sadly, as ever, humanity is playing its doleful part in destroying life on Earth. The Gobi, The Sahara, ‘desertification’ is, it seems, something we have caused. Or at the very least exacerbated.

We went for a walk at Castle Rising, after my afternoon shift today. Very nice.

I thought we might walk to the Castle itself. But we didn’t. Instead we walked down a lane, eventually reaching a bridge (below), and then turning back.

‘Twas a very pleasant stroll. And something I think we all needed and enjoyed.

Wow! The tidal wave of ‘new’ music continues. New to me, that is. Most of it, like this, is ages old. So far I’ve just listened to the opening few minutes. But they were very promising. I look for’ard to really digging in…