This may be a bit behind the times, butt…

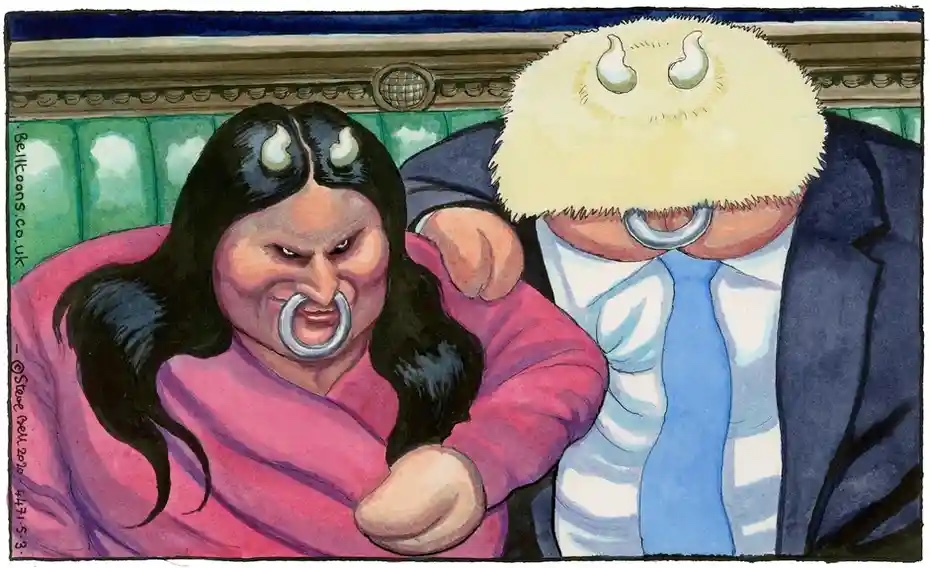

Ok, I love Steve Bell. I think his art is superb, and I think his political satire is and has long been very prescient. Both funny and cuttingly near the bone. Might it cause offence? Of course. And so it should.

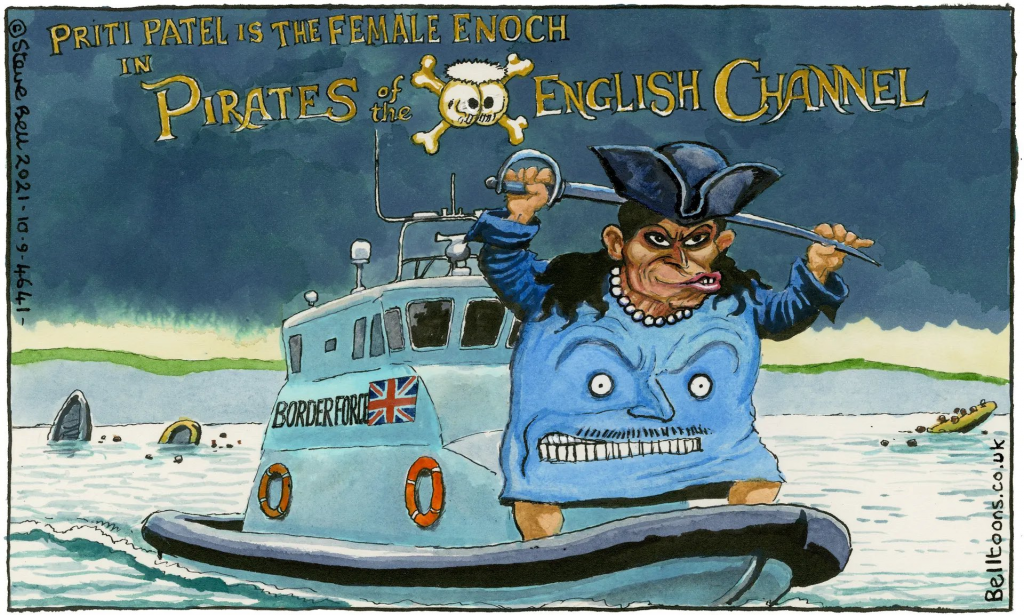

Is this image – cropped above, in full below – the same as Nazi imagery of Jews? Personally I really don’t think so. Is the core point of it to demonise Patel on ethnic/racial grounds? Of course not!

I will admit that it’s a long way from surprising, re the stink it kicked up. And it’s no surprise to hear that it’s those on the right, including religious folk, invoking ‘hate crime’ censorship of a left wing view they dislike.

Indoctrinated hordes of right wingers, of all ethnicities, might believe Jeremy Corbyn is a 50/50 blend of Stalin and Hitler. And that’s the kind of ludicrous fantasy propaganda modern satire ought to be able to help fight.

It’ll mostly be people willing to believe in that weaponising of ‘anti-semitism’, in what very clearly was a character assassination witch-hunt, which aimed at – and succeeded in – smearing a very anti-racist man* as the very thing he so frequently campaigned against, who are getting so upset by Bell’s cartoon.

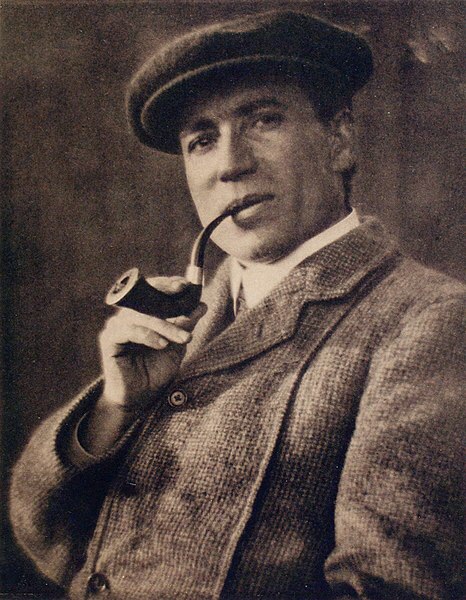

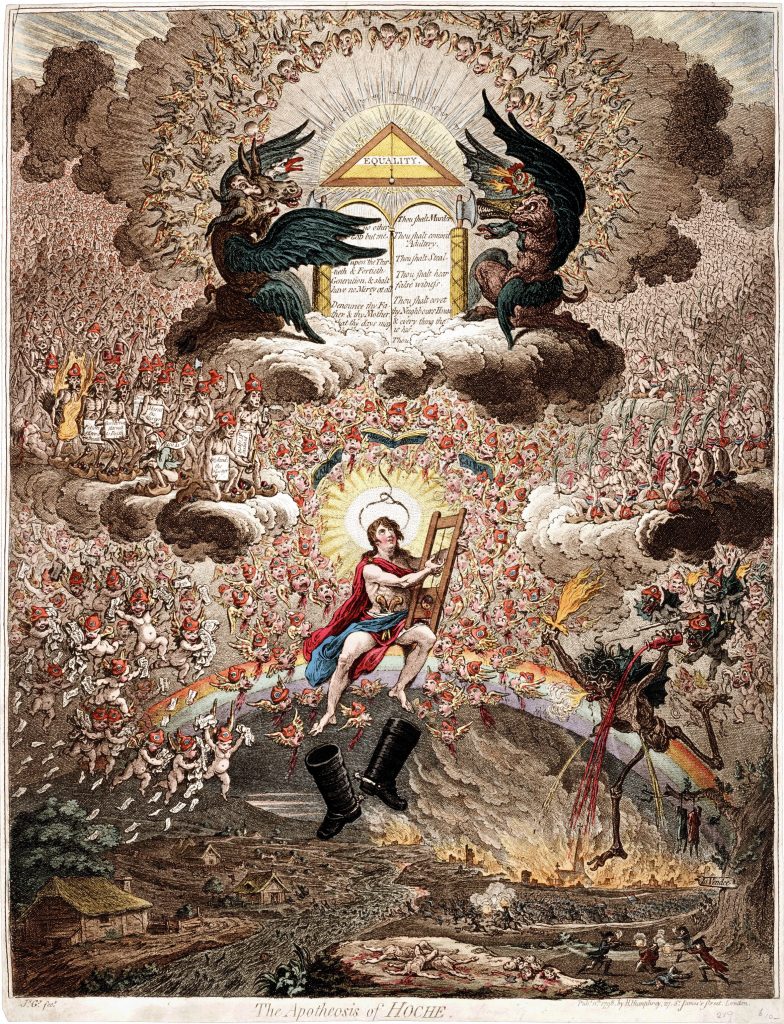

But, rather ironically, one of the greatest of all English print cartoon satirists, Gillray, was actually – for the most part – paid to produce satire that served the ruling Tory elite.

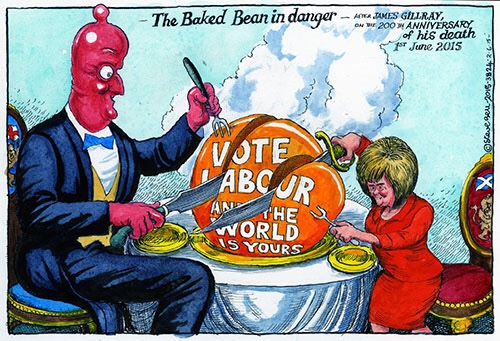

Bell has tipped his metaphorical tile to his antecedent and occasional inspiration, Gillray, sometimes reworking his imagery. I won’t say reworking ‘his ideas’, as usually Gillray, unlike Bell – the roles of artists have evolved! – was for the most part drawing to order, for his Tory patrons. And, just like modern Tories, Gillray’s paymasters abandoned him, after his years of sterling service, to poverty and insanity in the end.

It seems, in a way that has echoes of Clarkson getting sacked by the BBC – not remotely similar in many ways, and yet… – that the Guardian, like the BBC, is willing to lose a ‘long-term asset’ in order to ‘move with the times’. Whether either decision was primarily based on ethical concerns or not… who knows? But in our venal times one tends to be sceptical!

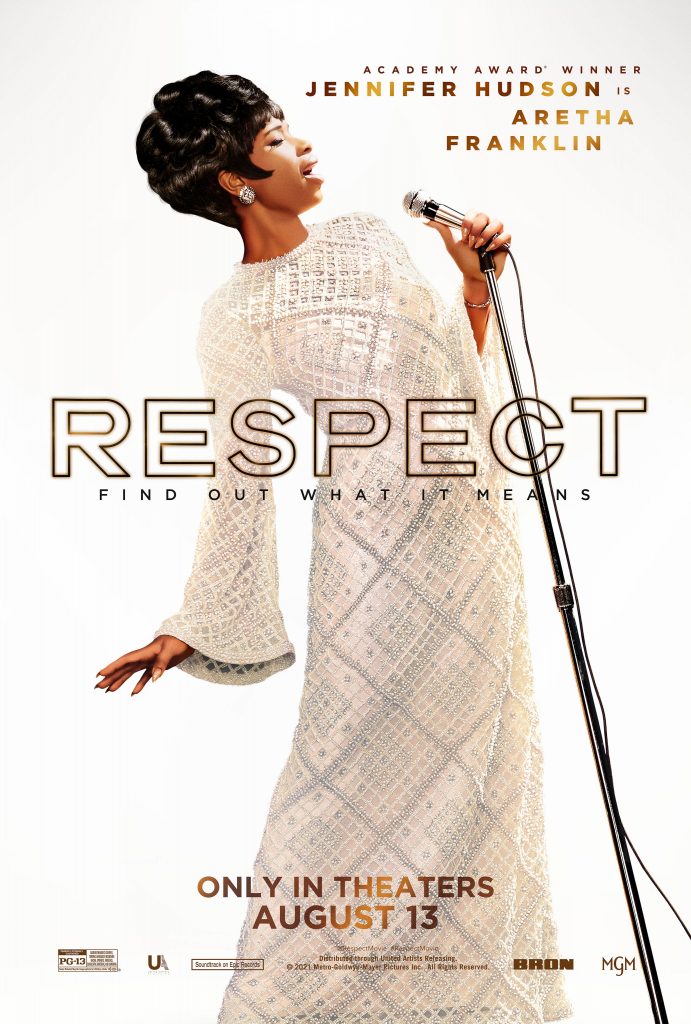

In the above ‘Female Enoch’ cartoon, Bell nicely captures a far more odious, real and deep rooted form of racism, as practiced by a woman ‘of colour’ in power. Just because she’s female, and of non-white ethnicity, doesn’t absolve her from the possibilities of racism, or even sexism, or indeed any -ism.

Indeed, as Spitting Image lampoon, in one (or more) of their recent satirical episodes, having members of ‘out groups’ or traditionally discriminated against ‘minority groups’ in positions of power, can help the ruling elite camouflage their oppression of the groups these favoured individuals appear to belong to.

Thatcher did precious little for women’s rights, aside from the mere fact of being a woman in a traditionally male role. And to take the idea further, into the kind of fascist mud-slinging some on the right have the temerity to invoke, the Nazi’s loved to use favoured individuals from their victimised out-groups’ to lord it over the oppressed masses, infamously using fellow Jews as concentration camp Kapos.

I fear Patel and her Tory ilk, not for her ethnicity, but for the self-serving moral vacuum that’s where a human heart or conscience ought to be, far more than Steve Bell, who I don’t believe to be racist.

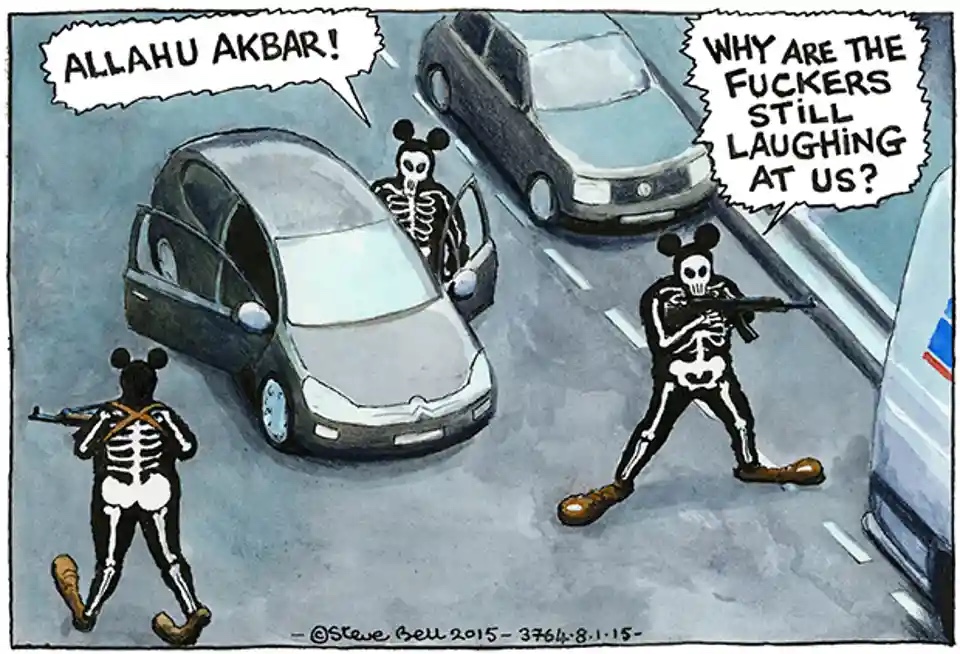

Would those attacking Bell’s satire approve of his being gunned down by an offended Hindu fundamentalist? And say he deserved such a fate? I don’t think such a thing is as likely as an equivalent scenario involving an enraged Muslim, in response to an image such as that below:

I’m with art critic Waldemar Januszczak, who tweeted thus in response to news of the Guardian not renewing Bell’s contract: ‘I worked with Steve Bell when I was at The Guardian. He was and is an evil genius. Anyone who thinks it’s a good idea to get rid of Steve Bell is a pitiful thinker. Pitiful.’ Amen to that.

Bell himself has said that his non-renewal at The Grauniad is, as far as he’s aware/concerned, due to economics, not ‘effin’ Patel’… or words to that effect!

* I’m no Corbynista, and I don’t claim he’s a paragon of perfection. l