Some time ago I wanted to make a proper egg-mayonnaise sandwich. So I ‘googled’ the topic. Particularly important was being able to peel the eggs without totally butchering them.

I found a really egg-cellent website, getcracking.com, which sorted me out on that front poifeckly.

This very useful web resource also suggested that readers try Doro Wat, an Ethiopian chicken curry recipe that uses hard-boiled eggs. So I’m going to cook it tonight, for us, and Dad and Claire.

… much later the same day.

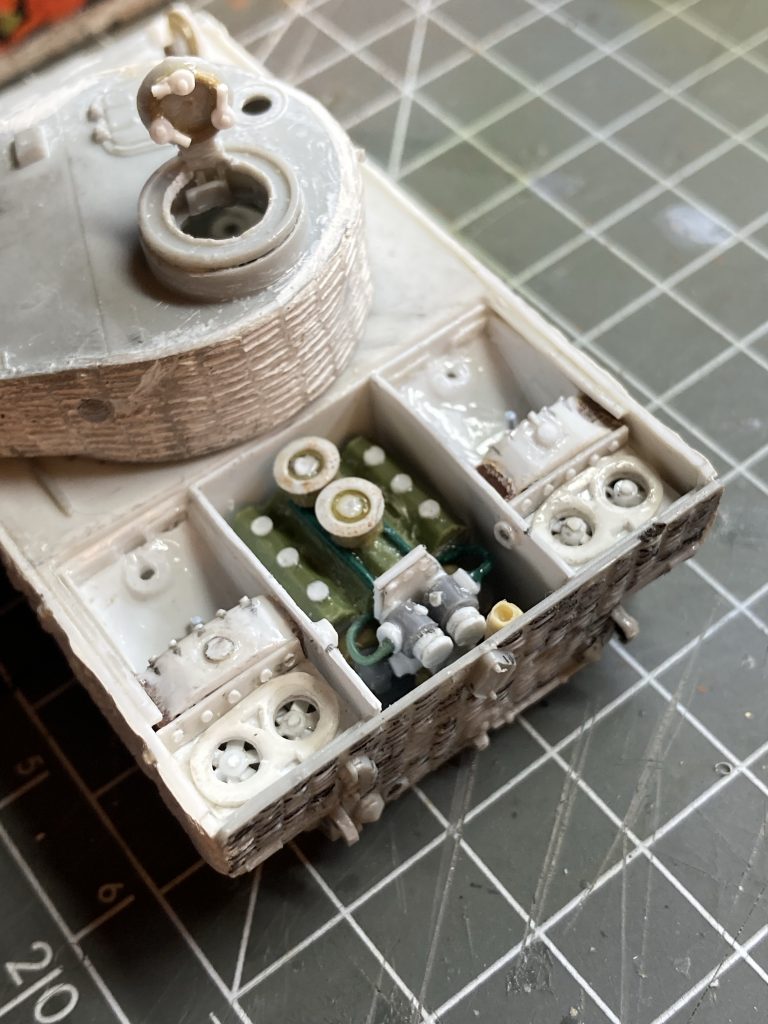

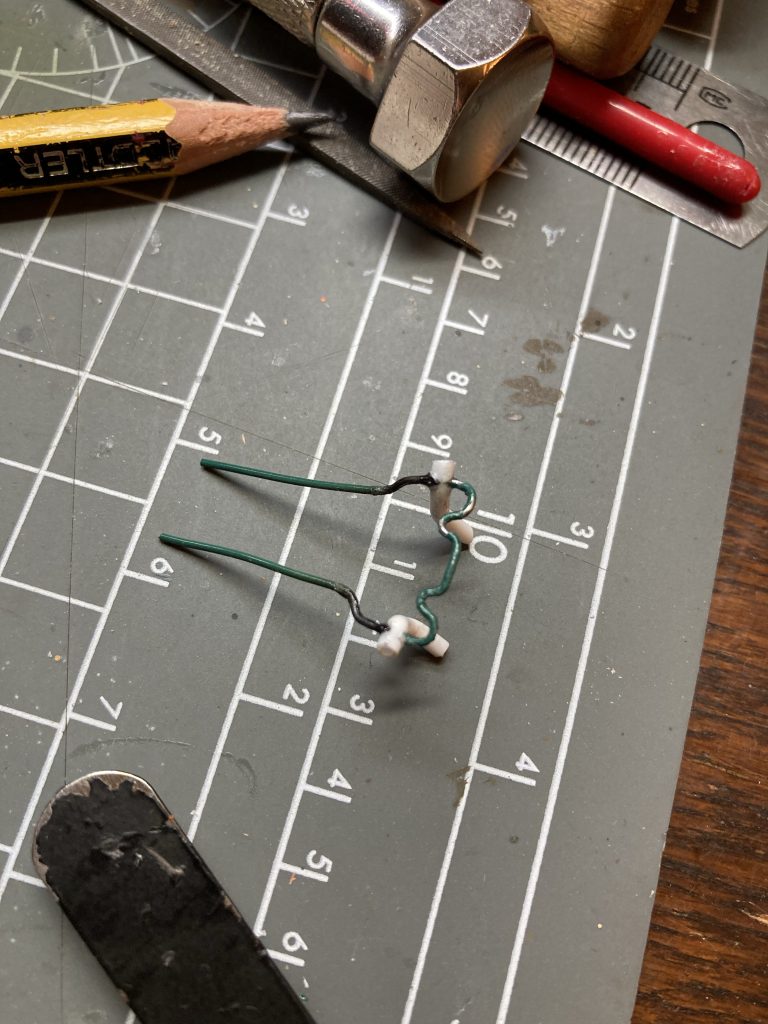

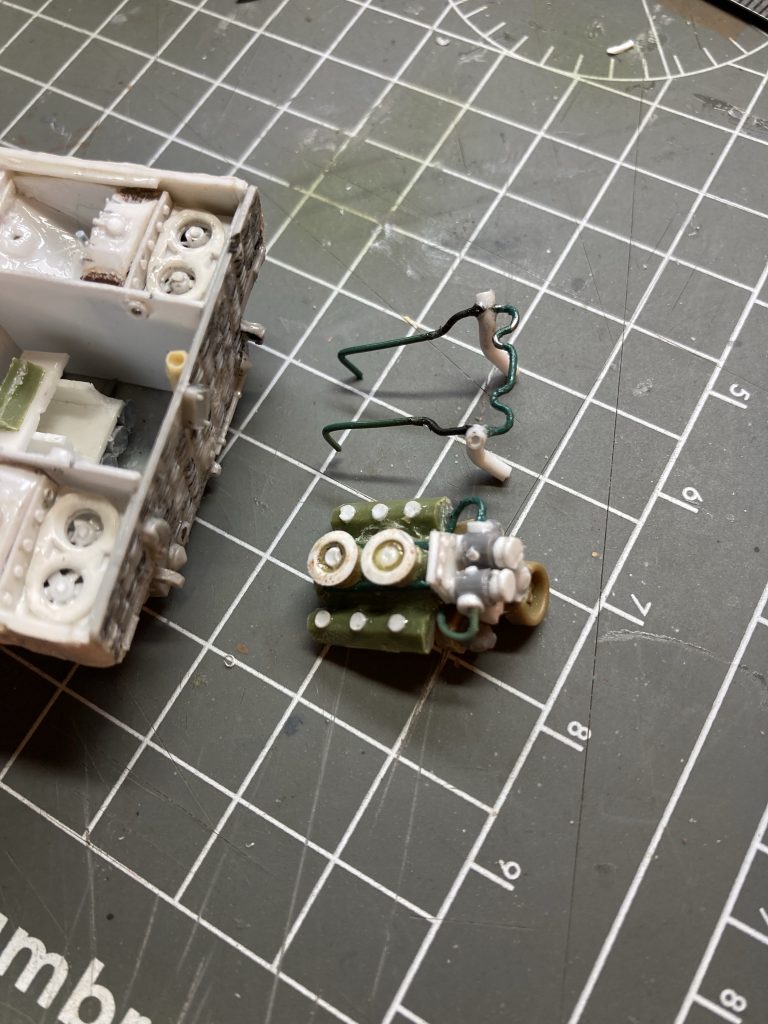

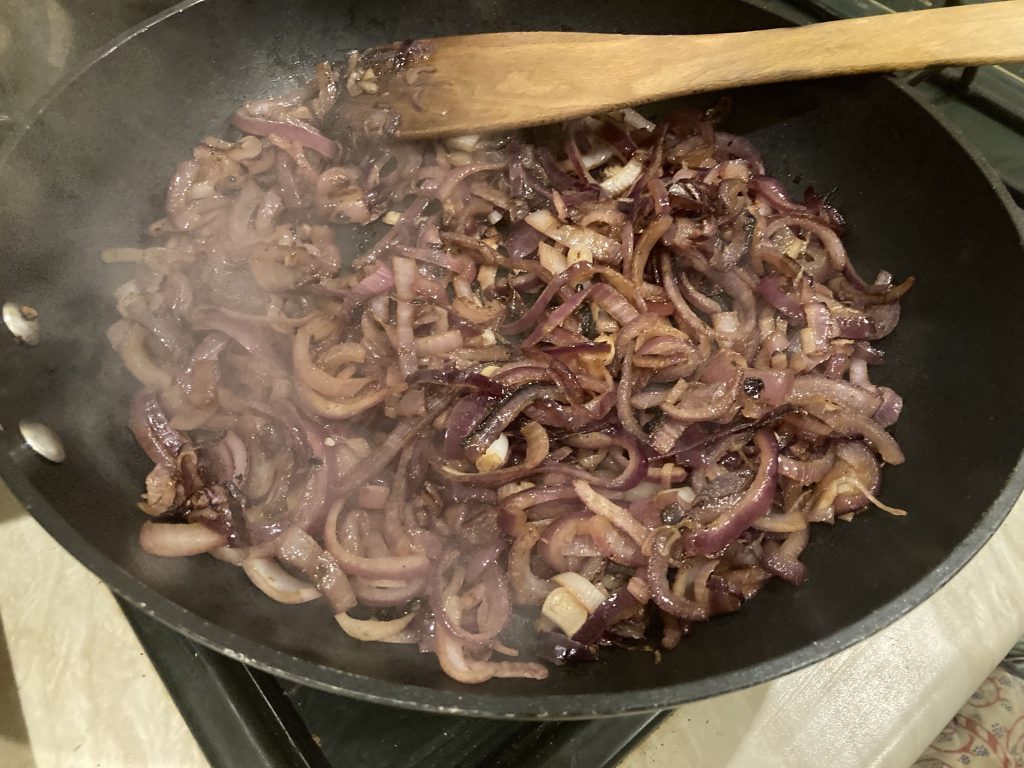

My own work, above; not looking quite as good or appetising as the getcracking.com example at the top of this post.

Dad and Claire did eat with us (sadly, brother Sam could’nae join us). And survived! If I made it again, I’d change it up a bit. I’d do chicken breast pieces, and brown them off earlier in the process, not huge bits on the bone and cookies at the very end. I’d add more ghee, and prob’ also more chilli, ginger, garlic and water.

If I’m totally honest, it was merely ok. Quite nice even. But perhaps not something to write home about? The ‘berbere’ spice mix – so many spices! – which smelt very fragrant initially, somehow didn’t quite pack the expected punch. Still, worth a shot. You live n’ learn!

Lovely to spend the evening with Dad and Claire as well. Plus, whenever we have guests round, an incidental benefit is that we will usually tidy the place up considerably.