Absolutely stunning!

Originally reviewed March, 2013, on Amazon UK. This version is slightly updated/revised.

Marcos Valle has been something of a musical chameleon over the years. Coming up in the second wave of bossa nova in the sixties, he could and did write in that form brilliantly, producing several albums, mostly in his native Brazil and sung in Portugese, but including Samba ’68 , recorded in the US and sung in English. As the sixties came to a close he and his brother, a songwriting team of rare excellence, began to experiment with broader ranges of sounds and lyrical themes, keeping bossa and samba in the mix, but gradually incorporating the broader themes of MPB*, various pop forms (rock, soul, soundtrack, funk), even psychedelia and Tropicalia.

* Music Popular Brazil!

Already he had behind him such eclectic masterpieces as his self-titled 1970 recording, and the utterly sublime Garra. With each new release there were increasing signs of a musically omnivorous diversity that would make categorising and describing Valle’s music ever harder. So far this hadn’t hurt his success, sales, or the critical reception that he was getting. Indeed, the brothers Valle were very busy commercially, writing music for the Brazilian franchise of Sesame Street (Vila Sesamo), an album for an airline (Fly Cruzeiro), and frequent commissions for TV and movie soundtracks, which often pop up on their albums.

Feeling the pressure of such demands, the brothers Valle (acc. to Allmusic) decamped to the hippie beach town of Buzios, where they continued to collaborate, and not just with each other, but a really quite broad collection of fellow Brazilian musicians, and Vento Sul (South Wind) was the result.

Personally I feel that Valle’s music between 1970-4 reaches a peak the likes of which is rarely attained in popular music. As I type this Bodas de Sangue is playing: the fifth track on the album, it’s a sublimely beautiful instrumental that moves through several segments, ranging from filmic, to classical chamber music. From this they effortlessly segue into the baroque pop psychedelia of Demoscustico, in which a very rhythmic and phonetic poem is declaimed, over a musical background that continually morphs from section to section, in a dizzying but satisfyingly homogenous way. It really is stunning!

The title track is gorgeous, a lush, slow, gentle waltz. Marcos takes the lead vocal on this track. And that highlights another remarkable thing about this album; Valle doesn’t dominate the lead vocal spot on this album entirely, as he normally would. Several of the other musicians are just as prominent vocally on certain tracks, and a keynote of the recording is the amount of collective singing, such as that which takes over from Marcos after the first verse of the title track. It’s a literal musical embodiment of a kind of dreamy, gauzy, diaphanous hippie idealism made concrete in musical terms. Astonishing!

The musical range is also flabbergasting, many of the pieces are like little sonic worlds, the richness and the transitions so natural and beguiling one doesn’t always appreciate quite how amazing the range of the music is. At times it is quite challenging, as with parts of Democustico, or Rosto Barbado (Red Beard, on account of Valle’s emerging facial fuzz, perhaps?). Voo Cegoo and Mi Hermoza exemplify the strands where other vocalists, and group harmonies, dominate, with Marcos generously stepping back from the spotlight. Both are from the dreamier, mellower side of the repertoire, with the former being amongst my personal favourites, and the latter showing how far off his usual musical map Valle and co. were willing to travel, with Vinicius Cantauria and the musicians of O Terco stamping a psychedelic rock vibe on proceedings, especially in the fuzzed out rock section, with its distorted lead guitar.

I got the Japanese import version of Vento Sul (via Chicago’s dustygroove.com) some time ago, and it cost me a bomb. But it was very definitely worth every penny. That version of the album appends the wonderfully sunny and goofily upbeat O Beato as a bonus track.

I like O Beato a lot, but it kind of breaks the mood of gentle reverie that was created by the original final track, Deixa O Mundo E O Sol Entrar, which is a gorgeous song. Sung by Marcos, accompanied by several acoustic guitars, piano, electric bass and percussion, there’s almost some kind of Pink Floyd-esque feel at work, but with that jazzy Brazilian vibe thrown in. Fabulous!

Apparently all of this fabulousness was too much for the critics and Valle fans back in the day, and, bizarrely to my mind, Vento Sul marked a dip in Valle’s success at home in Brazil. But it has stood the test of time very well. Yes, it certainly sounds very much of its time, but in a truly wonderful way, showing what a creative and open era this was, even under the heel of the Brazilian military dictatorship of that era.

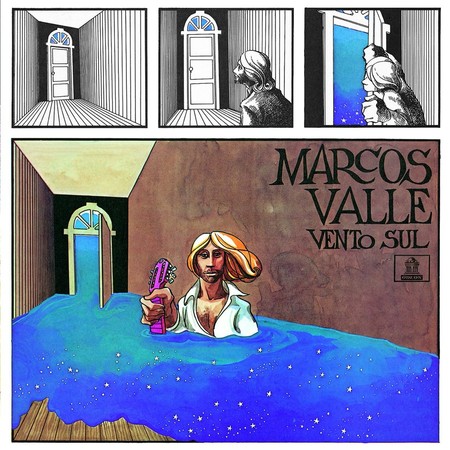

The beautiful cover painting conveys perfectly the dreamy feeling of this incredible album. If you like Valle, or just music brave enough to go its own way, this is a must have.