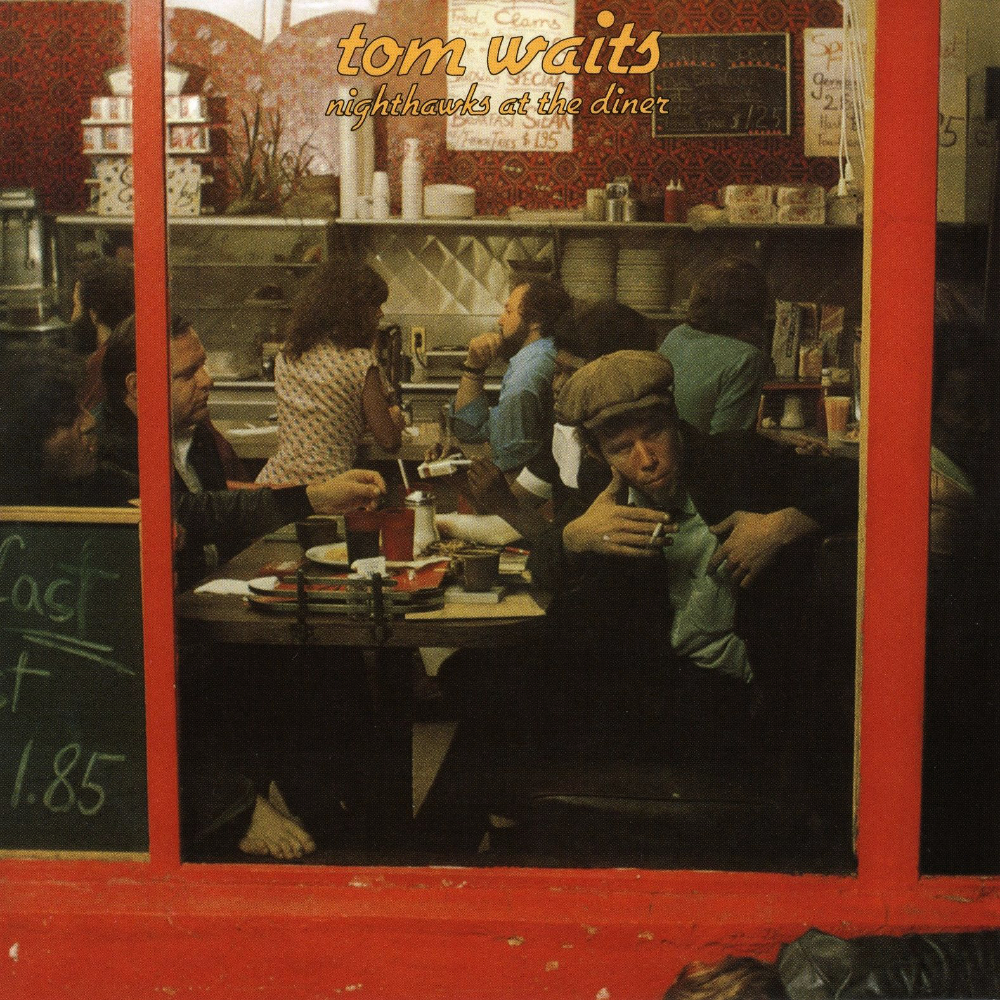

The 1970s, decade of the prog rock gatefold double-album, finds Tom getting in on the extended format action, but, as you’d expect, in his own inimitable way.

With only two – albeit utterly brilliant – studio albums under his belt, Waits was already heavily into paying his dues on the live circuit, and his shows were justly becoming something of a cult phenomenon, on account of three main factors: first of all his fabulous music; but, just as importantly, in terms of why his third release came out as a double live album, are the related facets of, secondly, his distinct charismatic persona and stage presence; and third, related to the latter, his marvellous way with words, or gift of the gab.

The effect of some pretty oddball and occasionally harsh live experiences, being inappropriately paired with everything from Vaudeville acts, or (not far from vaudeville, but some way off to the left of everything) with label mate Frank Zappa, had been to make Waits dig deeper into his beatnik persona, almost as a defensive shell. But it’s undoubtedly his pure gift for language, storytelling, and, ultimately, strange as it may sound, for someone so resolutely independent, showmanship, that lie behind this strange format for a third release.

Ever sensitive to bringing out the best in Waits, producer ‘Bones’ Howe was instrumental in making the recording happen, hiring an appropriate venue, and ensuring the right kind of crowd was on hand. Backed by a fabulous jazz band, Waits and co. deliver an evening’s worth of musical and lyrical magic, Waits mining his rich seam of imaginative and frequently very humorous storytelling to excellent effect.

There are so many great tracks, I won’t list them all; amongst my personal favourites are the moody cyclic semi-recitative ‘Upon A Foggy Night’, with Waits favouring 13ths and 7#5 chord voicings, giving the number a distinctly jazzy vibe, despite being delivered on a folk-style steel string acoustic guitar, and, whilst covers are something of a rarity in the Waits canon, it’s typical that when he does pick one, it’s an interesting and unusual choice; here it’s a sublimely evocative reading of country singer Red Sorvine’s ‘Big Joe & Phantom 309’, a tale of a saintly supernatural trucker, no less!

Hardcore fans of Waits will no doubt know that there are huge amounts of live Waits bootlegs out there, spanning his entire career, and of widely varied recording quality, so, retrospectively it was all the more prescient of Howe to ensure that a document of Waits in live and garrulous mode was captured in hi-fidelity, and we all owe him a debt of gratitude on that account. With more character than a convention of charisma competition winners, and a line in patter that’s got to be heard to be appreciated, this is a brilliant document of Waits doing his thing live: essential listening!