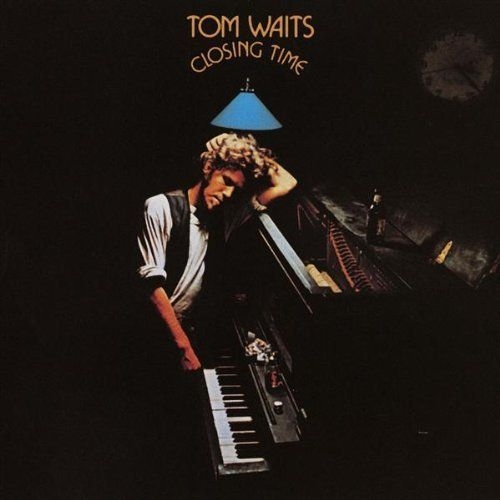

Here’s the first in a series of archival reviews of mine. This particular little series will cover ‘early’ Tom Waits, my favourite era from his now very long career.

As will readily be apparent, if you read on, I really dig this album. Tom is young and sweet sounding here, not yet the rasping fag and booze addled Beat, nor the boho-carni-freak of later or more recent years.

I personally think his entire output from this recording to Swordfishtrombones is nigh on perfect, and, for someone like me, it’s all essential soul-food listening. And each album is different, albeit there are threads that run through them all.

Waits’ wife Kathleen Brennan apparently came up with the term ‘grim reapers and grand weepers’ to describe two of the many faces Waits has commonly chosen to show in later years, and, of the two, most of the material from the early albums leans towards the ‘grand weepers’ side of that pairing. And that’s how I like it!

Produced by the maverick producer and musician Jerry Yester, who’s more associated with the roots-folk and psychedelic tinged sounds of 60s hippie-dom, this is something of an oddball or unusual album within the Waits canon. Given that, in many respects, he kept mining similar veins for some years to come, it’s a little tricky to pin down exactly why that is. It’s definitely something to do with the gentleness and soft innocence of his voice, especially in contrast to how that voice evolved, but it’s also in the unique sonic chemistry that the album has, even though later recording will revisit similar genre-based sounds, ranging from jazz, blues and folk, to country, and Tin Pan Alley style songs.

For a debut album it is, frankly, simply stunning – loaded with gems like ‘Ol 55’, ‘I Hope That I Don’t Fall In Love With You’, and ‘Rosie’, even the lesser tracks are still superb – and, albeit that they’re very different characters, it reminds me of Joni Mitchell’s debut, which, although ostensibly more of a fit with the times it was released in, is actually also very unique and personal. People pegged Joni as a folkster, and she saw herself as a composer. In a similar way, Tom is an artist, and that’s why, even though he long ago turned off the road of straight ahead boho-romance – the aspect of his work I’ve always loved the most – he remains a compelling figure.

Some of my personal favourites on this recording include the maudlin piano driven ‘Midnight Lullaby’, with the beautiful muted trumpet of either Tony Terran or Delbert Bennett (not sure who it is!), and the unholy trinity that ends the album, ‘Little Trip To Heaven (On The Wings Of Your Love)’ – the first of a long series of excellent tracks with long names using parentheses, that reaches it’s apotheosis on the Small Change album, with tracks like ‘Jitterbug Boy (Sharing a Curbstone with Chuck E. Weiss, Robert Marchese, Paul Body and The Mug and Artie)’, and ‘I Can’t Wait to Get Off Work (And See My Baby on Montgomery Avenue)’ – ‘Grapefruit Moon’, and ‘Closing Time’.

The musicians, mostly associates of Yester, perform the material with a magical sympathy and affinity that belies the fact that the band was, in essence, a pick-up outfit. This said, drummer John Seiter and upright bassist Bill Plummer had been playing together for six months prior to the recording, possibly with Yester’s band Rosebud, which had recently come to an end, but I’m not sure about this. But given how different the music they were playing elsewhere was, they rise to Waits muse with real verve and grace. And, interestingly, so does artist Cal Schenkel, better known for his work on Zappa’s record covers. Here he turns in a picture perfect evocation of Waits as the last to leave, as it comes to closing time.

According to Jerry Yester, quoted by Barney Hoskyns in his excellent biography of Waits, Lowside of the Road , there was an awed silence at the end of a take of the instrumental track ‘Closing Time’, that gives the album its name: ‘That was absolutely the most magical session I’ve ever been involved with,’ Yester recalls, ‘at the end of it no one spoke for what felt like five minutes, either in the booth or out in the room. No one budged. Nobody wanted that moment to end.’ Yep, I know that feeling, I’ve had it often enough listening to many Waits records, not least of which is this.

If you’re as big a Waits nut as I am, you might have some of his live bootlegs, and you might notice that, whilst numerous tracks from this album make the occasional appearance in his live repertoire, the achingly beautiful ‘Closing Time’ itself is a rarity. The only instance I know of being for the BBC in 1979. In a way the rarity of it makes it even more special. And I think that is perhaps a fitting epitaph to the recording itself.