‘The islanders have always been a mongrel race and we are the stronger for it.’

![]()

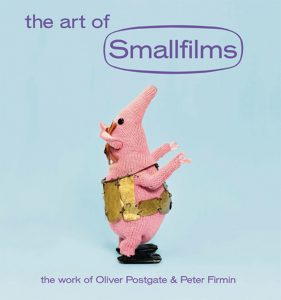

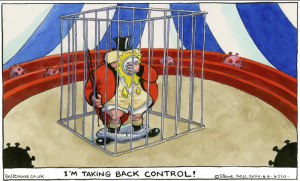

NB: I originally wrote this review around 2012, when I was sent the book to review as part of the Amazon Vine program. But, in the light of Brexit, I wanted to re-post the review here on my blog.

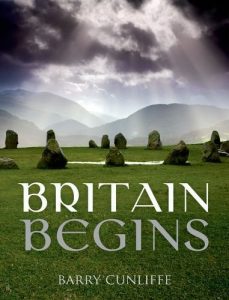

Wow! This book is a fascinating and exciting compendium of diverse facts, beautifully illustrated, telling the most incredible story.

Cunliffe writes with great clarity and engaging straightforwardness, weaving together various strands of scientific deduction sufficient to put Sherlock in the shade. What science there is here is, on the whole, easy enough to follow. Certainly this isn’t too drily technical a read. Indeed, throughout the book we often touch upon moments connecting us with our forebears, a very early and poignant instance of this being the discovery of Mesolithic footprints in the littoral muds of Formby point.

Covering 11,000 years, from the retreat of the ice around 10,000 BC (when these lands were still connected to the European continent), to the arrival of the Normans in 1066, Cunliffe tells how the people of these islands grew from bands of a few hundred hunter-gatherers to a mixed population of around two million. Before embarking on this epic tale he sets out what we used to tell ourselves was our history, from the first mentions of these lands in ancient Greek and Roman texts, through to indigenous writers like Geoffrey of Monmouth, examining how myth and fact interwove, before beginning on the journey to the more complex and nuanced understanding we have now.

More than half of the book is given over to the period prior to these islands entering into the written record, which Cunliffe describes as formerly belonging to ‘shadowy pseudo-history’. It’s quite moving reading Geoffrey of Monmouth, who belongs to this earlier semi-mythical phase, saying ‘Britain, the best of islands… provides in unfailing plenty everything that is suited to the use of human beings’, and then having Cunliffe, the modern post-enlightenment scholar concur, stating that indeed, ‘The British Isles … occupy a very favoured position in the world’, and explaining why this is so (geology & climate).

At around 500 pages, with a very substantial ‘further reading’ section at the back, this is a serious book. But despite the books size, as Cunliffe concedes, his scope is so huge that it remains a very general and brisk overview of a huge subject. Chapters often conclude with summarising statements, which is helpful, and there are three ‘interlude’ chapters, dealing with such topics as language and religion. As he says in his preface, ‘An archaeologist writing of the past must be constantly aware that the past is, in truth, unknowable. The best we can do is to offer approximations based on the fragments of hard evidence that we have to hand, ever conscious that we are interpreters. Like the myth-makers of the distant past, we are creating stories about our origins and our ancestors conditioned by the world in which we live’.

Unsurprisingly the nearest lands have been those to most consistently stock our genetic banks, with arrivals coming from land masses we now know as Spain, France, the Low Countries, Germany and Scandinavia, and in the Roman period an even wider ranging area. The first 9,000 years of this story are couched more in terms of generalities and theories, drawing primarily on the longer standing practice of antiquarianism, or what evolved into archaeology as we now know it, but also other associated areas, some of which, like our growing knowledge of genetics, are much more modern developments. The parts dealing with the last millennia become more like the kind of history many of us will know from school or general reading, with tales of kings and queens, war and invasion.

The ‘innate mobility of humankind … inherent in our genetic makeup’ is a continuing theme throughout, existing in constant tension with the domesticating aspect of human culture, as waves of invaders and colonists seek first to find new territories and then to live in them. Throughout this continual ebb and flow human and material traffic continues, leaving behind trails of artefacts and monuments, from grand buildings to everyday waste. Rather like the amazing detective work of Darwin, this is a tale concerned with origins, and it’s amazing what we can deduce from a close examination of the world around us, and how much that world can still tell us of our past.

As a generally interested reader of history I found this an extraordinary, fascinating, and very compelling read, fabulously supplemented by a rich array of graphic material. Loved it!