As a work of art, and labour of love, this is a five star affair. So why have I, rather meanly, knocked off a half star?

Well, the truth is that I really rather dislike – though in truth that’s not a strong enough word, detest is better – the Bible. The over-reverence, or even just plain attention, that it is accorded, even by it’s critics, is energy that could be better spent on other things. [1]

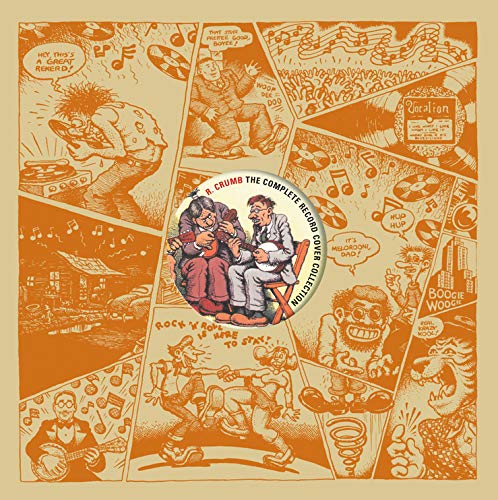

The task of illustrating Genesis took Crumb about five years, according to the artist himself. And it was a challenge in numerous ways; he wanted to draw in a more ‘realistic’ and historically accurate manner than he might sometimes adopt in other works, and this was to be a ‘neutral’ even-handed rendering. Neither the drooling sycophancy of the acolyte, nor the cutting satire of critical disbelief.

Both of these factors impact on the total work of art. Fans of Crumb’s more celebrated stylised exaggerations might find his style here a bit straight-laced. But, truth be told, I reckon his pure passion for rendering decent art wins out. And enough of his slightly icky primitivism seeps through to keep it well within ‘signature Crumb’ territory (he already has a strong tradition of cartoon as documentary, from his prolific sketching to his histories of early jazz, blues and folk musicians).

And then there’s the actual Biblical content. Some of it, such as the most colourful and celebrated mythical parts, like the Creation, the Flood, Joseph in Egypt, etc, is perfect material for Crumb. But there are other aspects – in particular the lineages – which are a part of the Bible, in particular the Old Testament, that I’ve always loathed.

So, whilst Crumb’s art itself, and his sheer chutzpah in even attempting such a project, are all five star, the material itself is considerably less. The importance of the Bible in history, as great as it undoubtedly has become, is, nevertheless, continually overstated. It’s position, rather like it’s very genesis (pun intended), is one of those accidents of evolution; it just so happened, rather than the texts winning a place in history by merit, never mind Divine authorship!

Having said all that I have, I’m intending to read Isaac Asimov’s two part Biblical work as soon as time allows. My excuse for this Judaeo-Christian navel-gazing and time wasting is the working out/off of my own very religious childhood.

As works about the Bible go, this is undoubtedly a very good one. The way Crumb treats it, very literally and completely, is a good antidote to either the fawning reverence of believers, or the sometimes overly gleeful mockery of the disbelievers.

Believers might, one hopes, start to sense the human historicity of their founding text, and we can all marvel at the sheer nuttiness or banality of certain parts, or even cogitate on the potentially more profound ‘psychological truths’ (should you feel that way inclined) of some of the potential readings of certain foundational myths.

In addition to an intro or preface (I forget exactly how he titles it!), there are Crumb’s ‘commentary’ notes on the text, at the end. This stuff reveals Crumb’s own take on it all more clearly, as someone with a secular historical interest in his source material. There’s a particularly interesting thread in here regarding how certain textual oddities might result from a later patriarchally slanted redaction of originally more mixed stories, some of which would have (or might have) originally had a decidedly more matriarchal slant. Fascinating!

If you’re a Crumb fan, or interested in the history of religion/myth, and I’m both, I’d say this is well worth having and/or reading.

——————

NOTES:

[1] It’s a ‘pop culture’ thing; why endless genuflecting before The Beatles, or Dylan, or Miles, or even Bach or Mozart? Hero worship always requires lowering of critical faculties, a kind of group reverential hysteria takes over, and masses of ‘lesser’ stuff gets swept aside and ignored. To the loss of all.